|

Rhythm in Life and in Popular Art in Sicily

Alberto Favara Originally published as “Il ritmo nella vita e nell’arte popolare in Sicilia.” Rivista d’Italia XXVI, 1923, 79–99; re-published in Scritti sulla musica popolare siciliana - Con un’appendice di scritti di U. Ojetti, C. Bellaigue, E. Romagnoli e A. Della Corte, edited by T. Samonà Favara, 86–120. Roma: De Santis, 1959. Draft translation: Sally Davies, copy-editing: Kristen Wolf. I have long been aware of the existence of a law of applied mechanics that determines the organic structure of each animal species on the basis of the movements they need to live and survive. I also know that every organ has its own steady rhythm and normal movement, regulated by an oscillation that depends on its shape and weight. Furthermore, I also know that our actions and movements are always governed by rhythm, such as when our muscles alternately contract and relax, or in the automatic formation of the rhythmic period, in the small movements that initiate and follow a major effort. Our organs are endowed with the faculty to adapt, meaning that all movements are refined by all those secondary unnecessary actions and optimized by all those useful ones, until they become perfect and automatic. This is all done in an involuntary manner, since rhythm cannot be regulated by our will as it lacks the notion of duration. And finally, I was also aware that movement has a psychological determinism, related to the search for plastic beauty. However, all this theoretical knowledge actually falls quite short of the mark, and obviously I have never been able to put it personally to the test, since nobody can exclude the disrupting presence of human volition from the whole experience. I therefore decided to study the rhythmic phenomenon in the outside world, to observe my objective surroundings and take notes. This was how I managed to discover a whole series of elementary manifestations of rhythm in the vast lands of Sicily. The first example was in the anninniata di li jenchi, literally the “lullabying of the bullocks”.

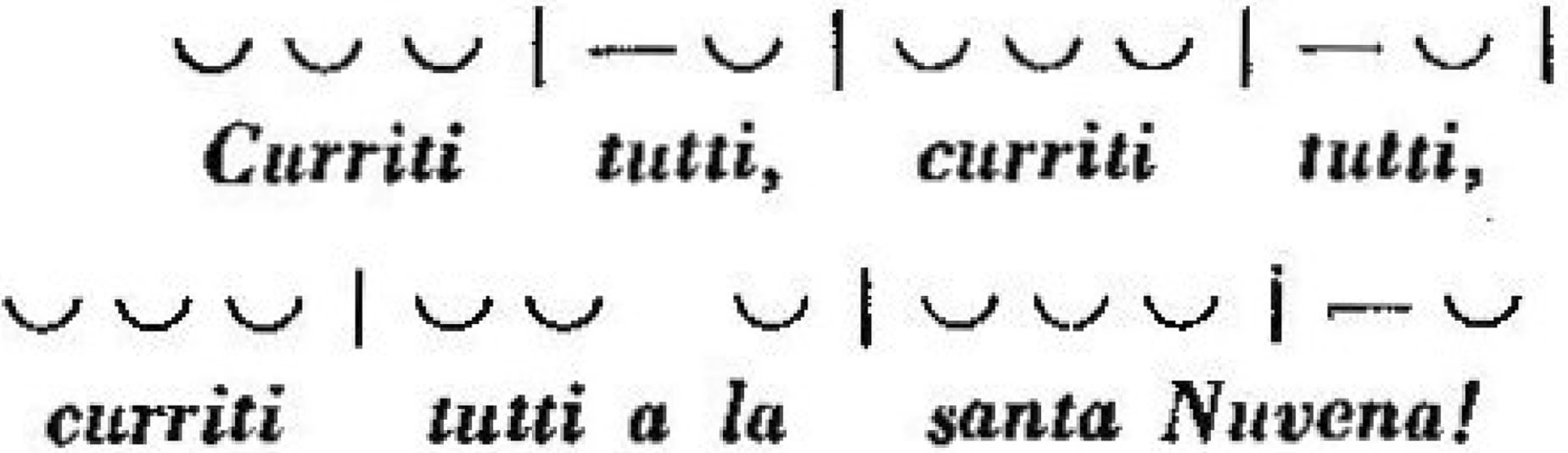

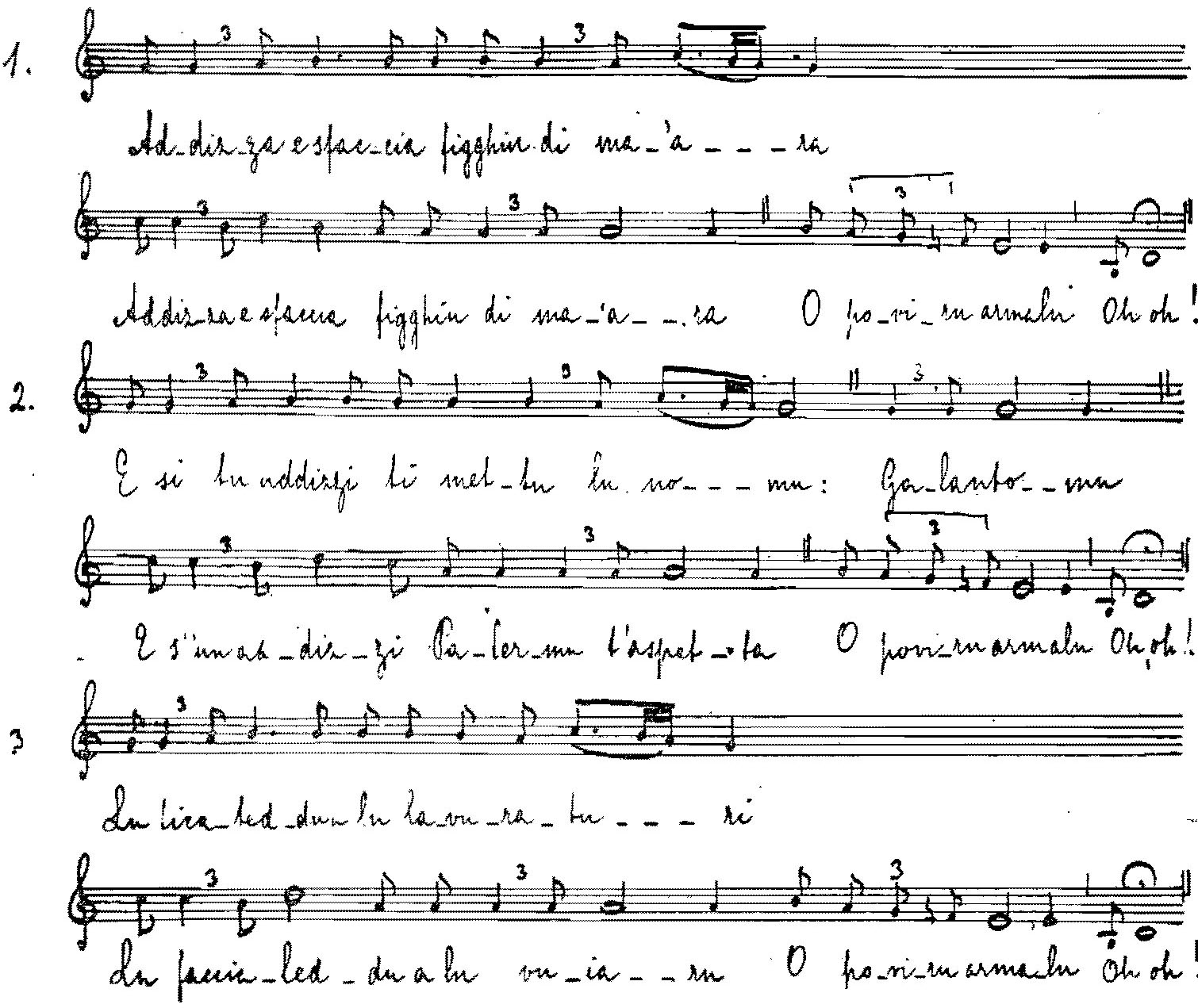

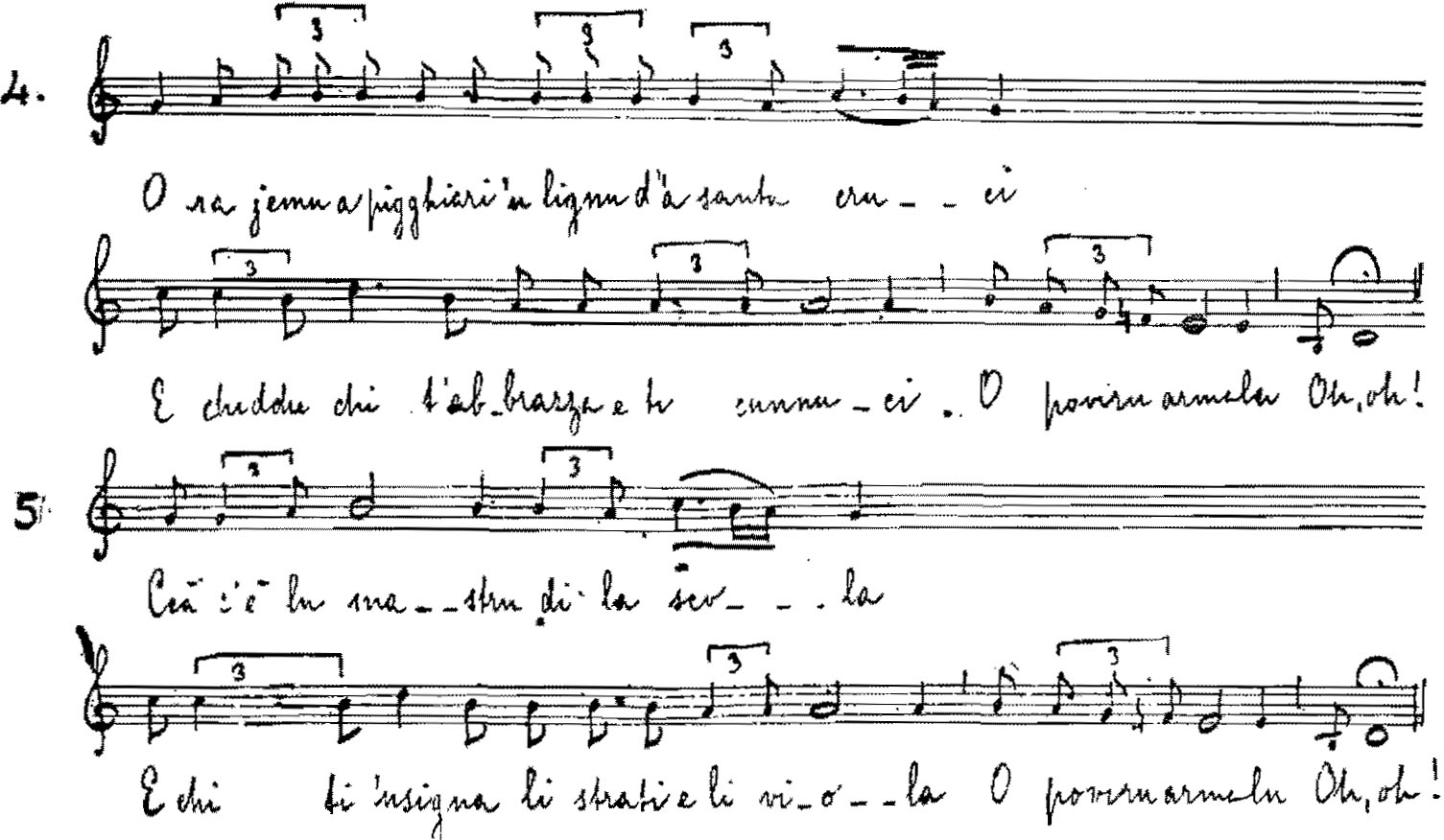

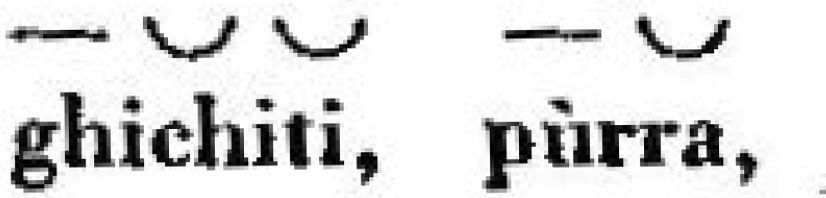

As autumn is drawing to a close, the wild bullocks are yoked to the plough. After a moment of rebellion through the bare earth, the animal is lassoed and then harnessed to the yoke – the percia – the handle, and the ploughshare by the cowherd and his helpers. This is all done in a series of traditional gestures, in rites that Alberto Favara have been handed down unchanged from ancient Sicilian ancestors. The animal turns side-on, lowers its head and backs away, emitting long drawn-out bellows as if he were mourning for his lost freedom. Then the lullabying begins, a majestic and solemn psalmody which turns this primitive struggle into a religious ritual. The song scolds, threatens, cajoles: “Working is the law, o poor animal! If you don’t pull straight, death will come, o poor animal! ” And the chanting goes on all day long for a whole week and the bullock listens. It forms an iambic pattern of forward impulses: “addizza e sfaccia” [on and on we go], and the melody acts as a sort of lubricant for these living creatures, mitigating the physical effort. This harmonious charm gradually calms the animal down and he starts to move in an orderly fashion, more suitable for the purpose: a picca a picca l'armalu si addizza [slowly but surely, the animal goes straight]. At last, the black and fertile furrow, the origin of every human culture, is opened up in Mother Earth, from whose bowels the frisson of the melody rises.

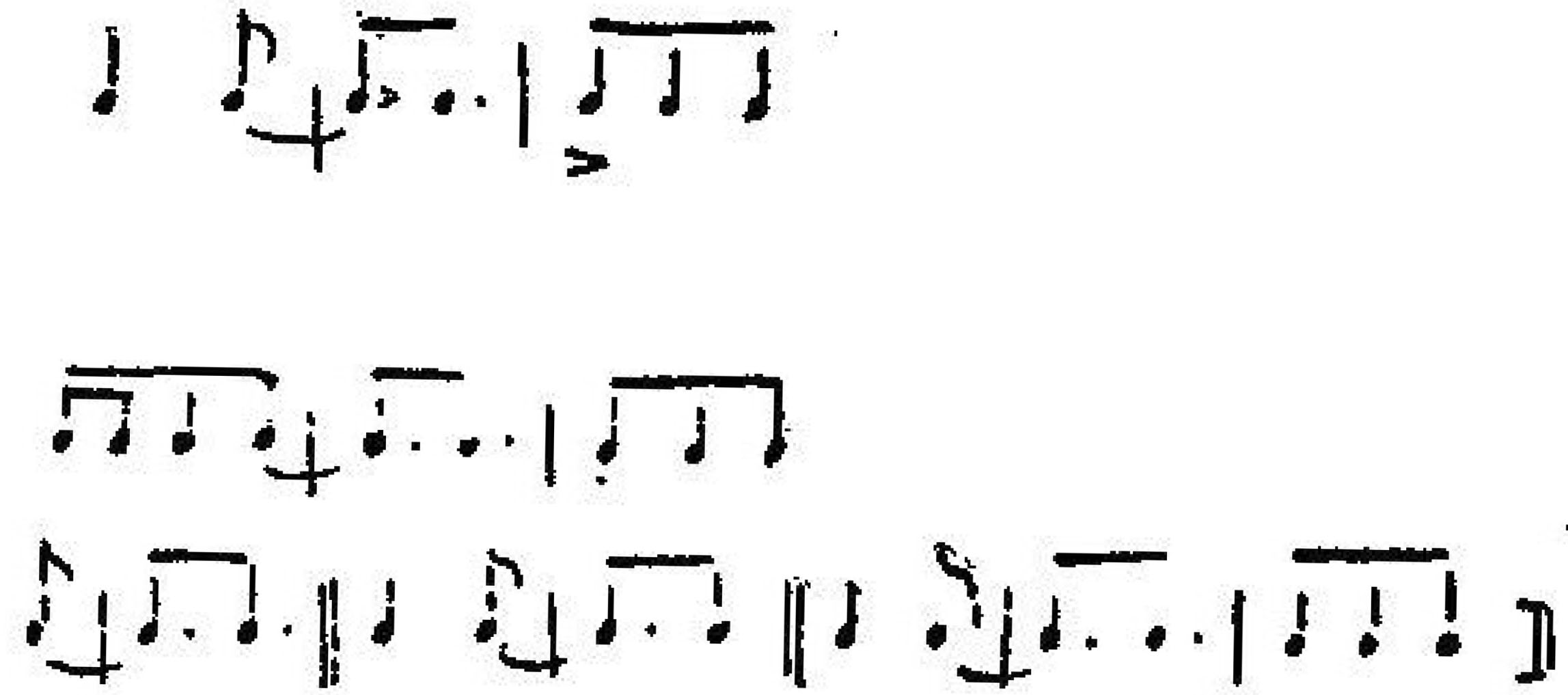

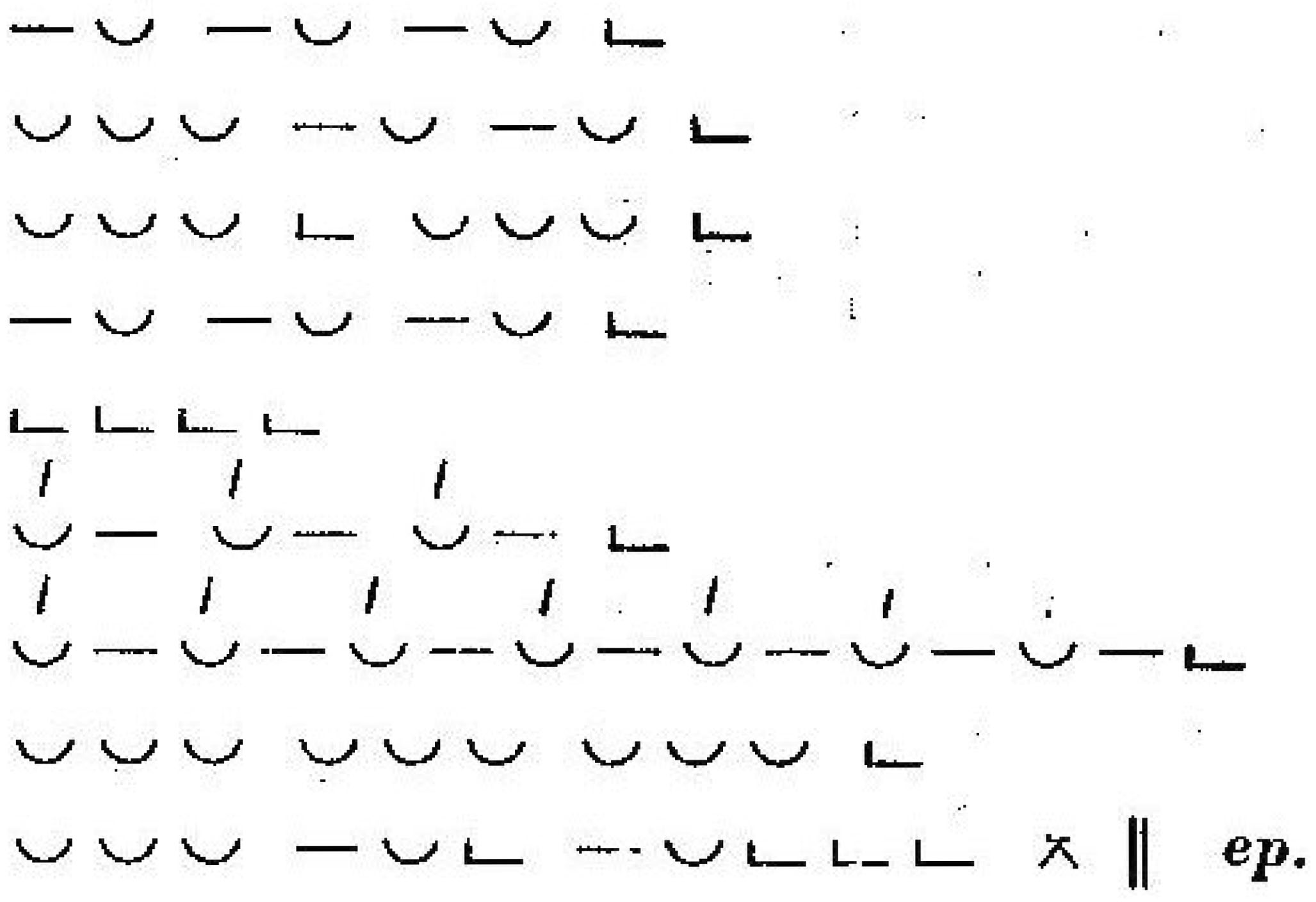

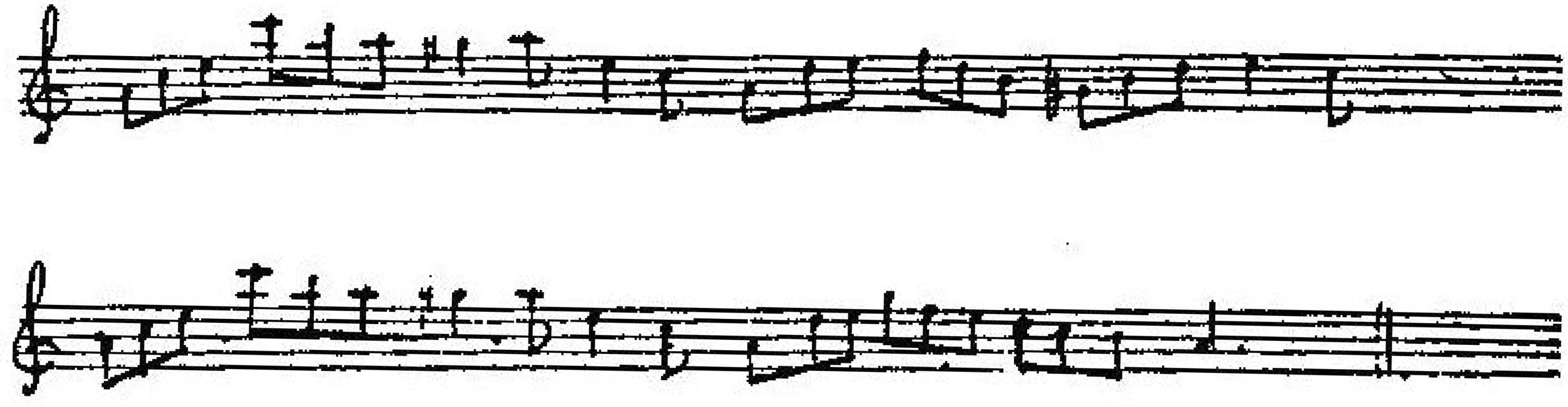

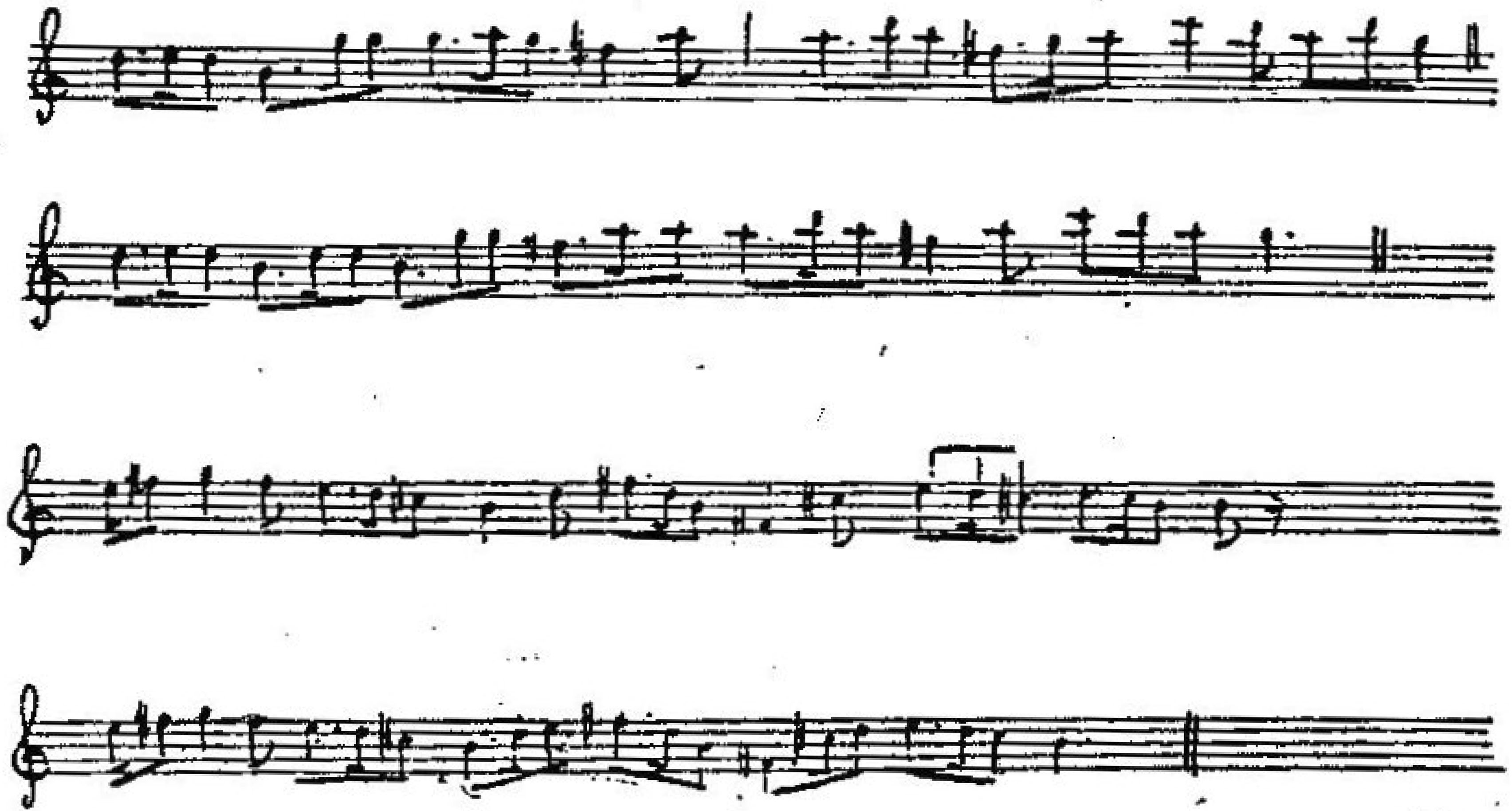

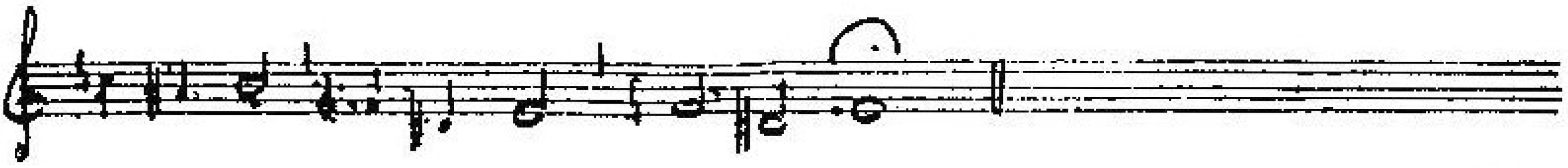

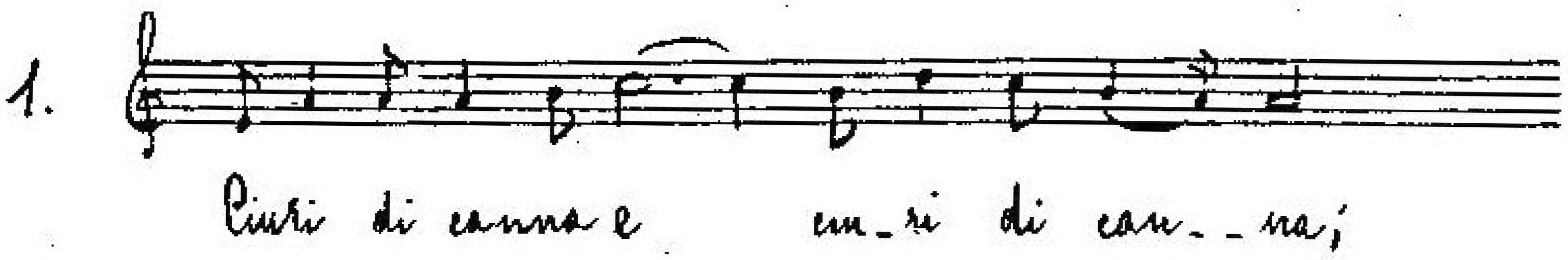

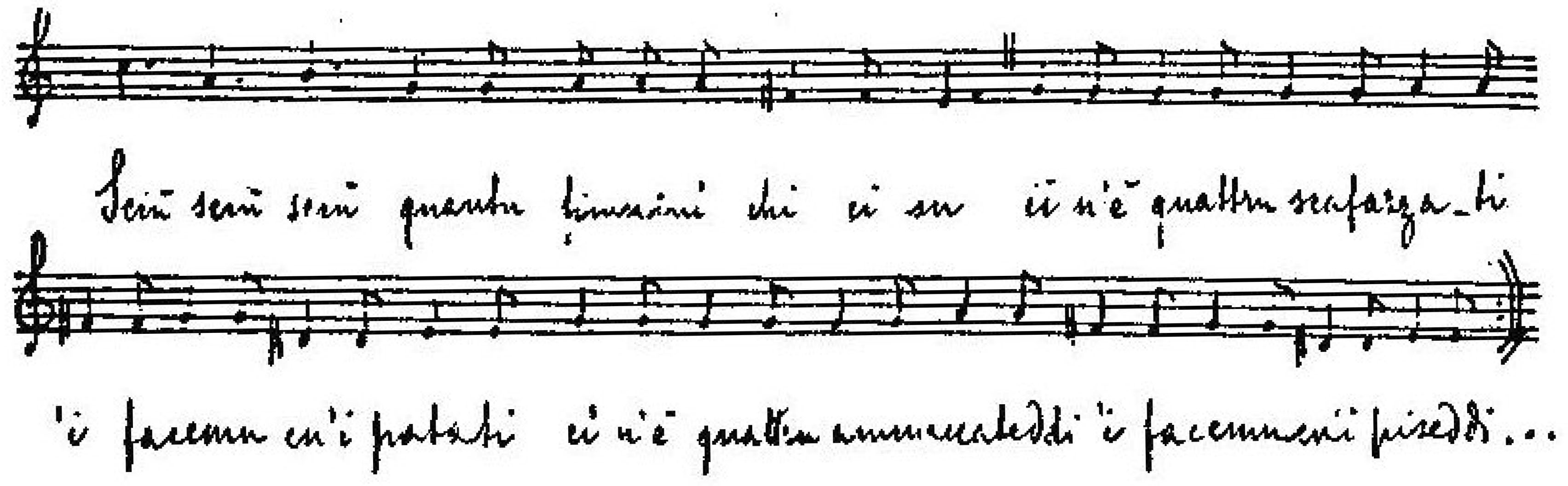

LULLABYING THE BULLOCKS

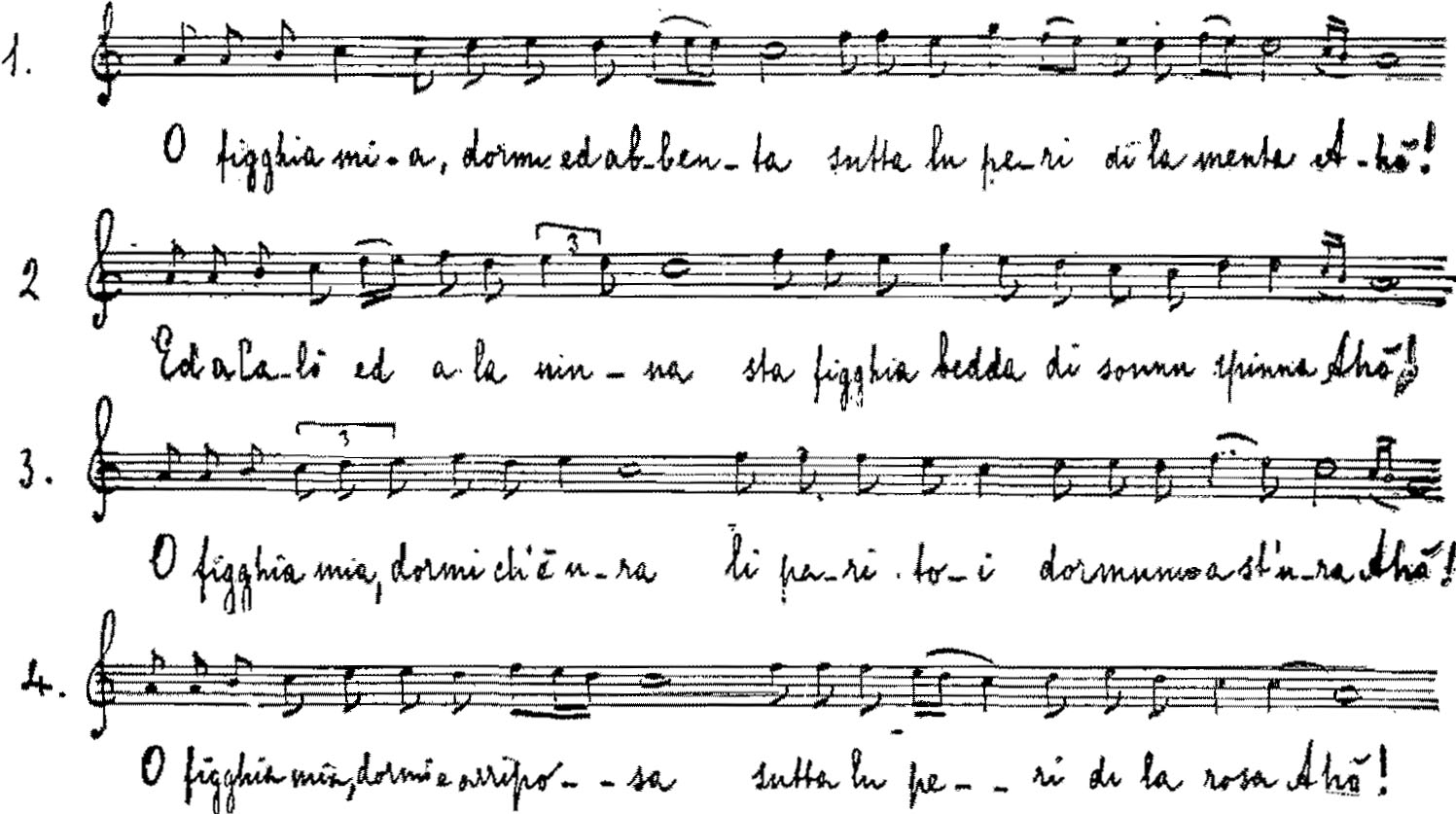

THE LULLABY OF SALEMI

More than the production of a strictly isochronous rhythm, music brings about a preliminary elimination of the disordered and violent movements of the living being. Both the anninniata di li jenchi and the lullaby from Salemi have the hesychastic ethos of Greek theory, where the modality and rhythm of a melody have a marvellous soothing effect, which was so often described by writers of ancient times. I have also noticed this same ethos in the instrumental melody that the herdsmen from Partanna on the Frattàsa platea play on their zufoli [pipes] at sunset, to call their herds to gather to rest under the oak trees.

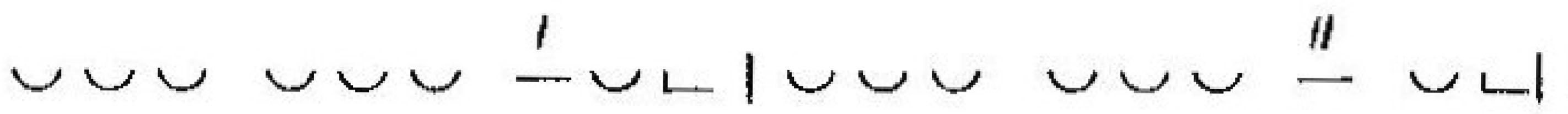

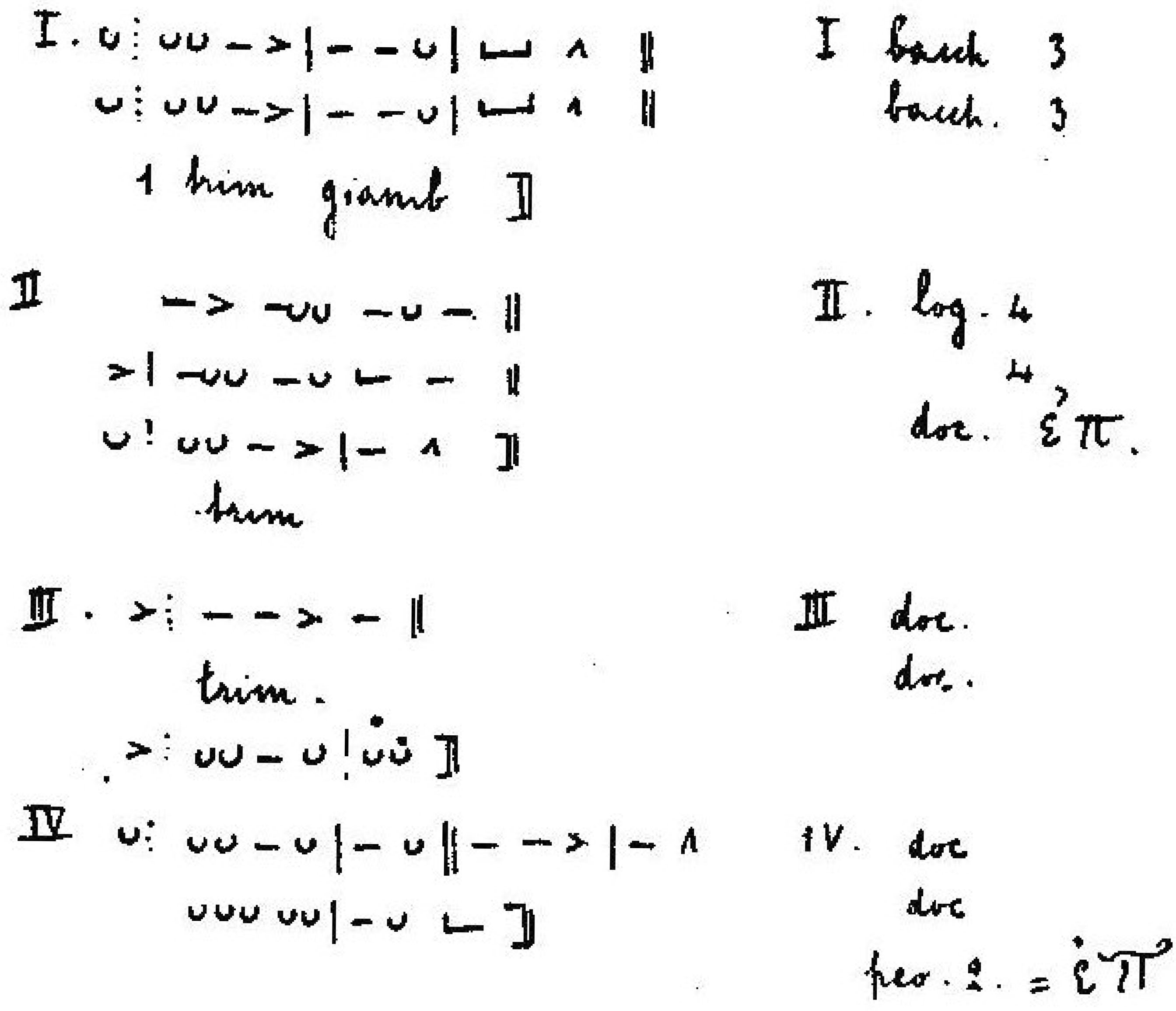

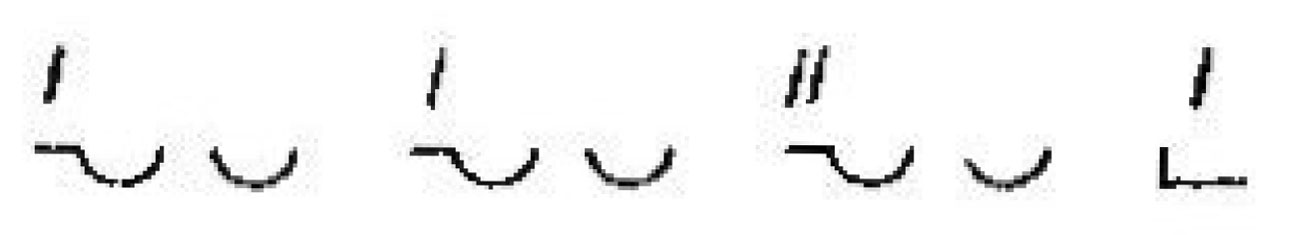

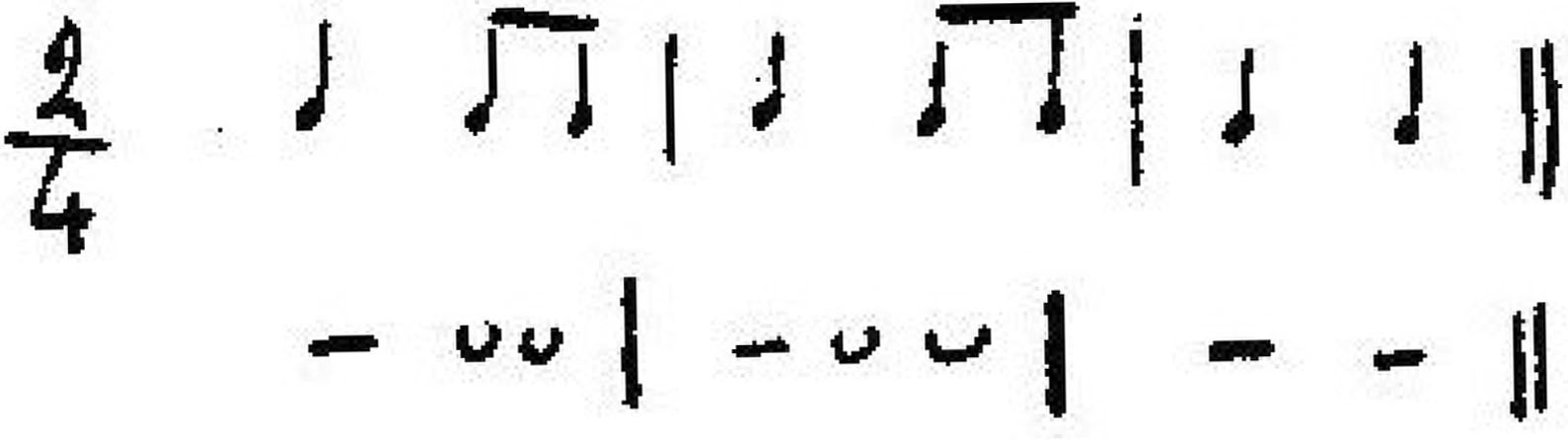

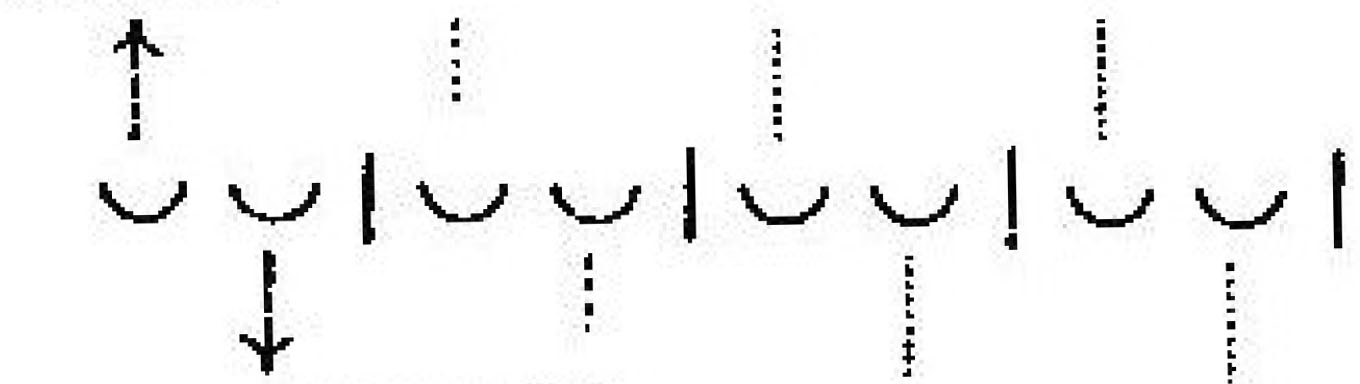

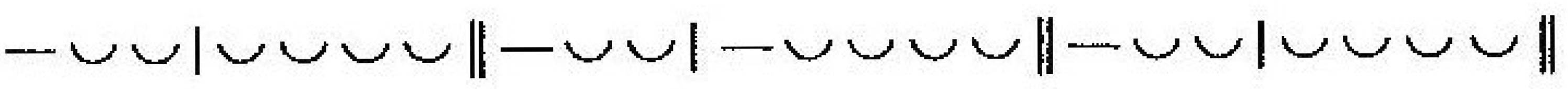

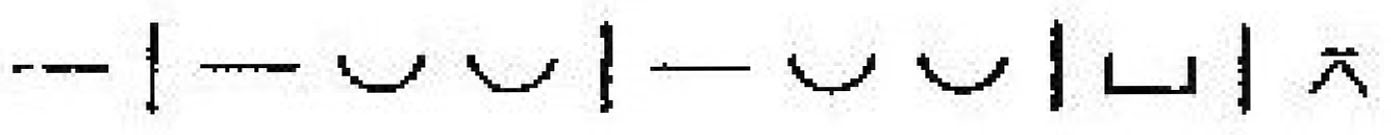

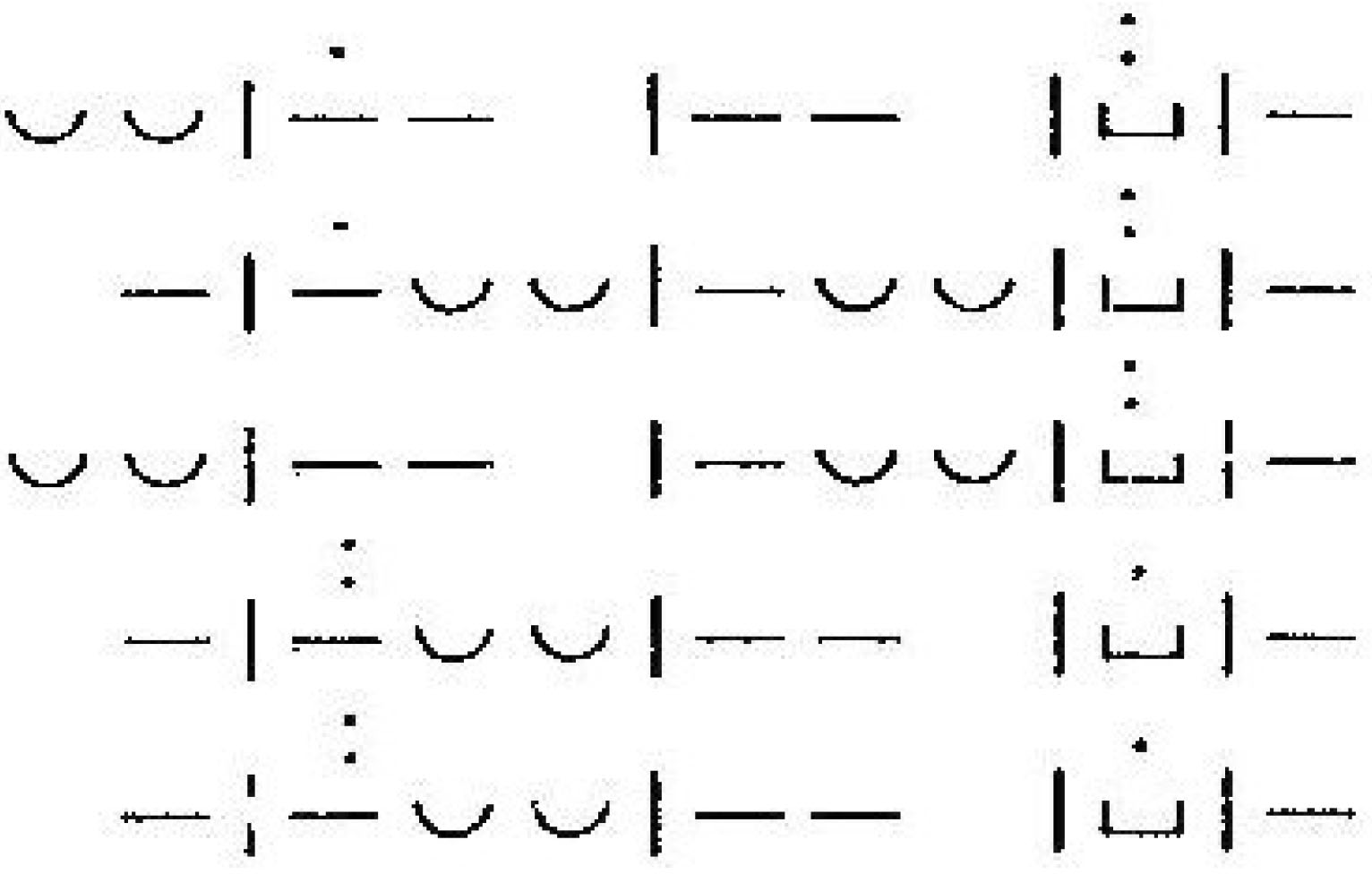

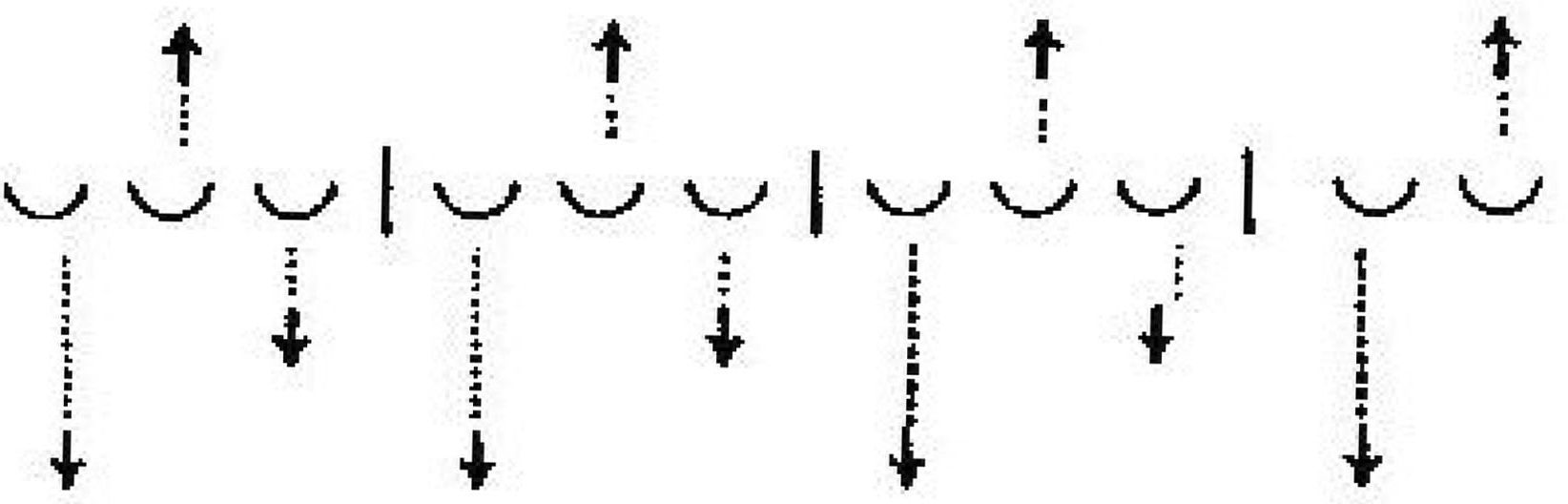

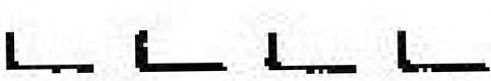

A smith strikes the iron with a series of blows from his hammer; the normal speed of these blows is due to the weight of the smith’s arm and the hammer, which the laws of muscle movement make equidistant. Finally, energy is regained at equal time intervals which causes an accent and, hence, the strokes are divided into successive periods:

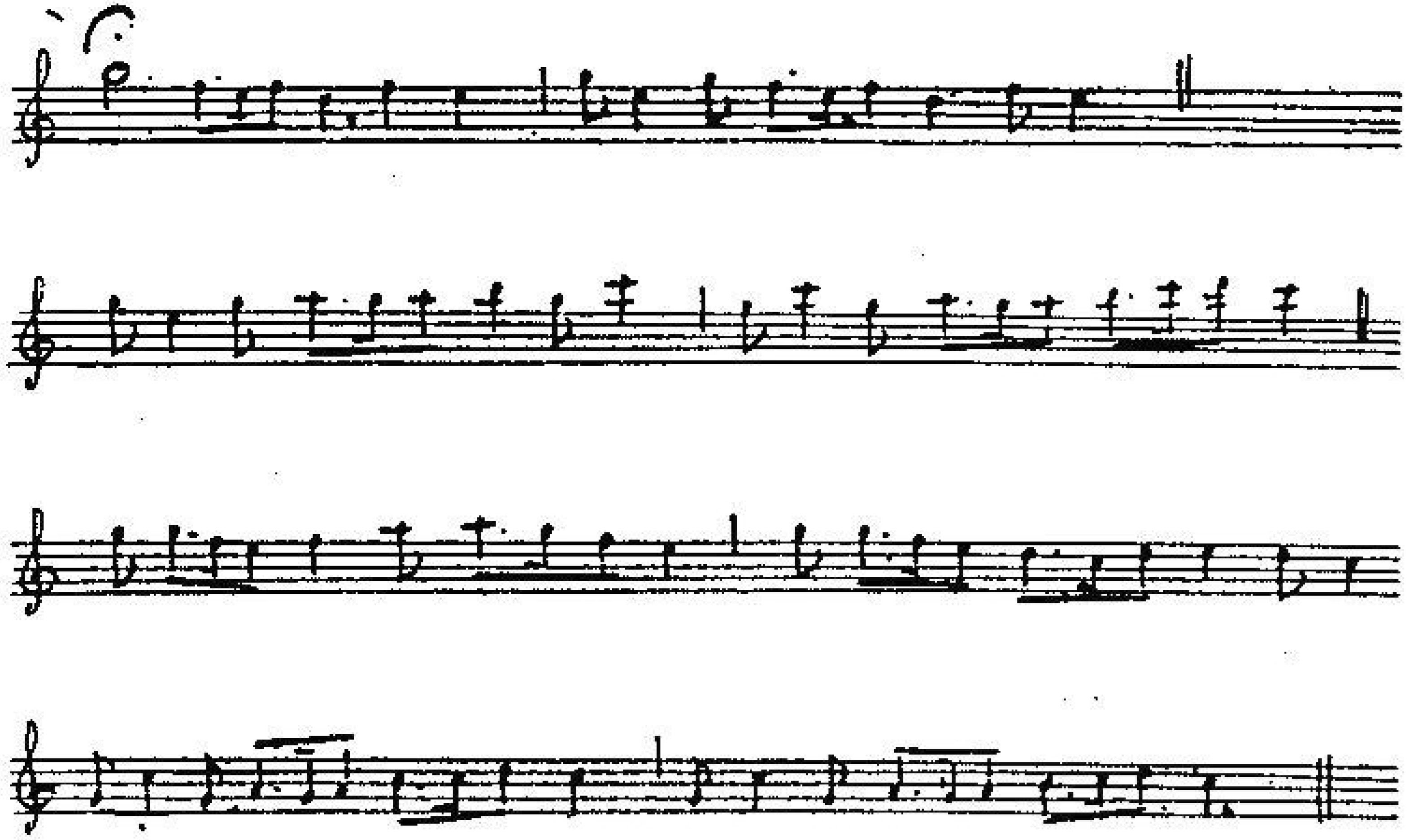

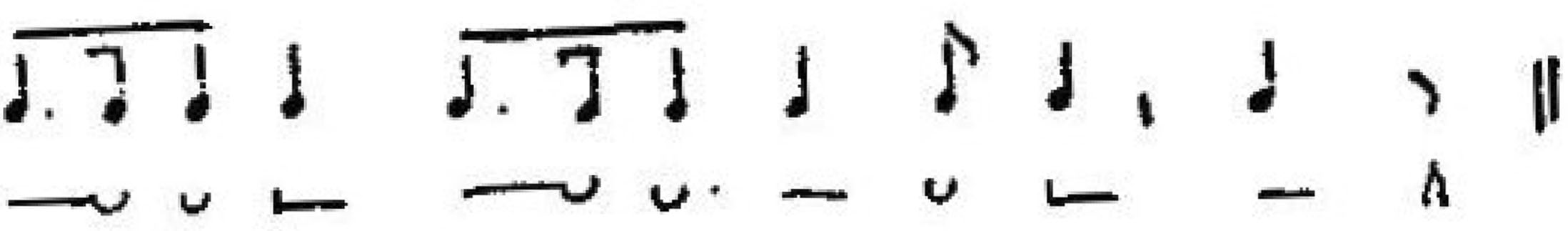

Here is the sonata a 2 martelli [2 hammer sonata] I found in Salemi and Palermo. There are two workers: lu mastru di forgia, the master, and lu battimazza, his apprentice. The smith has a small hammer in his right hand and uses his left to hold the red-hot iron on the anvil; the apprentice holds a sledgehammer in both hands.

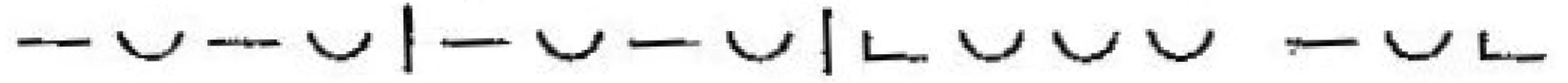

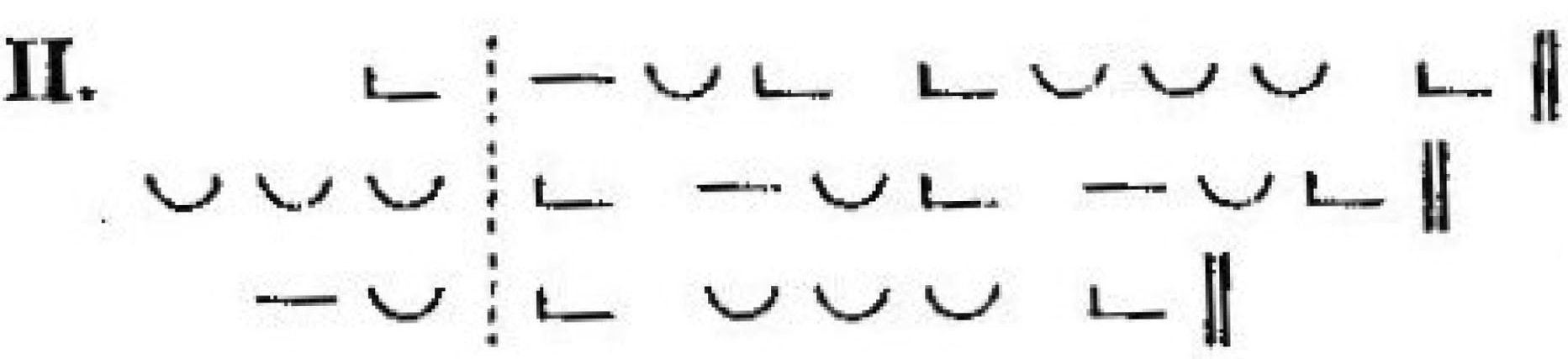

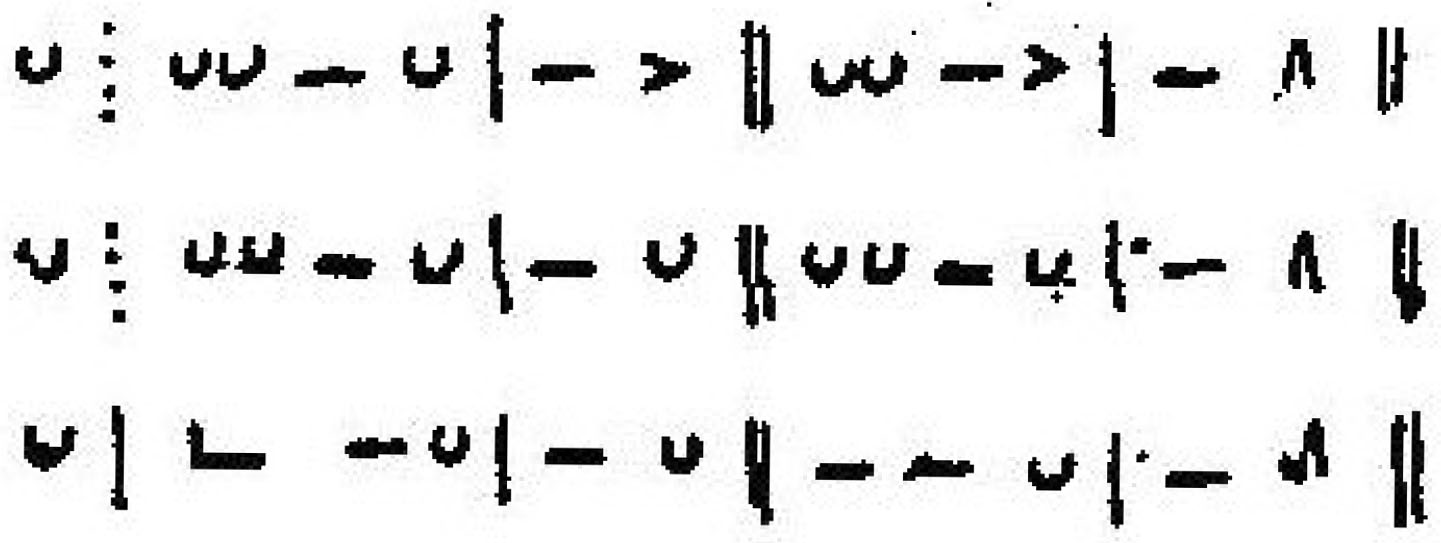

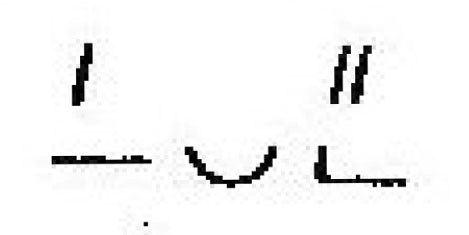

Attacco – The master taps the anvil a few times, three or four spondees:

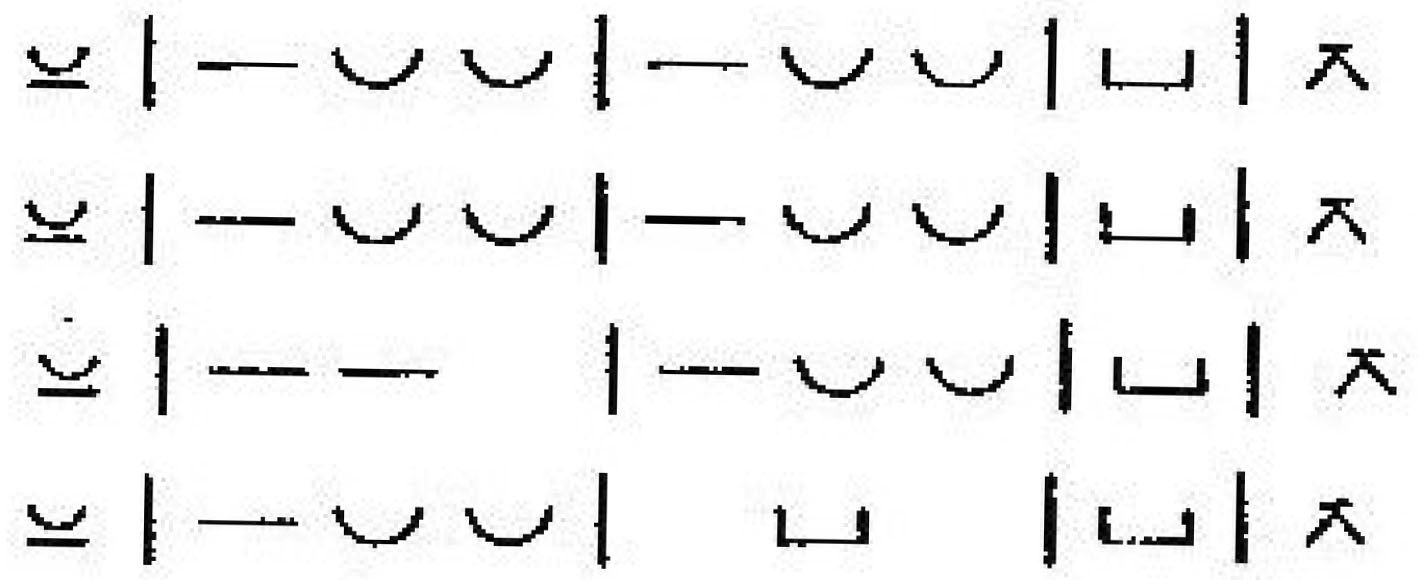

First motif – The sledgehammer and the hammer strike the red-hot iron in a rapid alternation which together form a series of simple proceleusmatics (Aristides Quintilianus: 34). The hammer continues to move as it did in the attacco, intercalated with the blows from the sledgehammer.

sledgehammer

Second motif – When the master-smith feels that the iron has been worked enough on one side and that it needs to be turned over, he directs his blows at the anvil, immediately followed by the apprentice. The two workers instinctively keep on hammering, since it would be difficult to suddenly interrupt their movements; indeed stopping and starting, instead of keeping on going would actually call for a greater effort. However, once the man with the sledgehammer is no longer directly involved in the working process, he rests by halving the number of blows he makes on the anvil: “pi pigghiari ciatu, pigghia 'no botta 'nta l'aria” [to get his breath back, he makes a stroke in the air]. Then the sledgehammer comes to rest supra la 'ncunia [on the anvil], while the hammer keeps on striking the same series of blows. This spontaneously gives rise to the following dactylic rhythmic form:

sledgehammer

This motif is called appellu, appellatina or staccamentu since it indicates the blows on the anvil, while the first motif is on the iron that is being worked. Once the iron is in its new position, hammering starts again in the first motif.

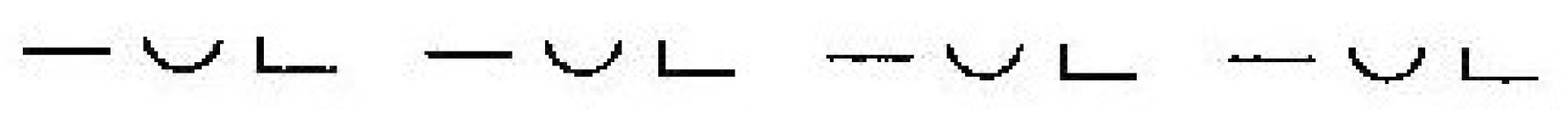

Although the tripody is the typical form of the appellatina, I also found a tetrapody in the 2-hammer sonata:

and a hexapody:

as well as the anacrusic forms:

hammer

hammer

A smith from Salemi saw the appellatina as having more than a practical working use. In his opinion, it differentiated between smiths and the boilermakers who always beat out proceleusmatics. He saw this distinction as being most important, as he considered his art of crafting ploughs, hoes, and weapons as a far nobler profession. Perhaps, he was voicing the primordial pride of the ancient Sicilian bronze-workers, who prepared the weapons for a population of horsemen who thirsted for war (Pindar, Nemean, 1). Furthermore, since metal-working in Sicily dates back to the oldest ages, as proved by Prof. Orsi’s archaeological excavations, we can be sure that the rhythms produced within this work have just as ancient origins. Moreover, the practical use of measure and proportion is enhanced by the sense of beauty that they spontaneously emanate. Our smiths feel the beauty of the anvil music, as they call it, and they understand its fundamental artistic importance: “Di ddocu, di la 'neunia, spuntau la musica; tutti li musichi spuntaru di ddocu“ [It is from there, from this selfsame anvil that music springs forth: it is where every kind of music is born]. These almost seem to be the words of some Greek scholar who is explaining the predominance of rhythm over the other elements in the musical arts, and things that are light years apart and yet identical are immediately brought together. The most ancient rhythm in Greek musical art is the dactylic tripody: in a flash, this coincidence takes us from the blacksmith’s sooty hovel to the Idaean caves. Here, the Dactyls mysteriously extracted metals from the bowels of the mountains and used fire to forge them to the rhythm which now takes their name. This mythical fact is now furnished with experimental proof, since it still exists today, as an unchangeable law that is there for all to see. It was to this rhythm, as strong and steady as the iron from whence it came, that the Apollonian culture developed triumphantly throughout the Mediterranean, from the priestly oracle to religious eulogies, from social and moral order to the Greek epic. This culture was hammered out in hexameters, in the midst of the smoke and flames of the mythical forge, pairing in a single line the tripodies beaten out on the anvil.

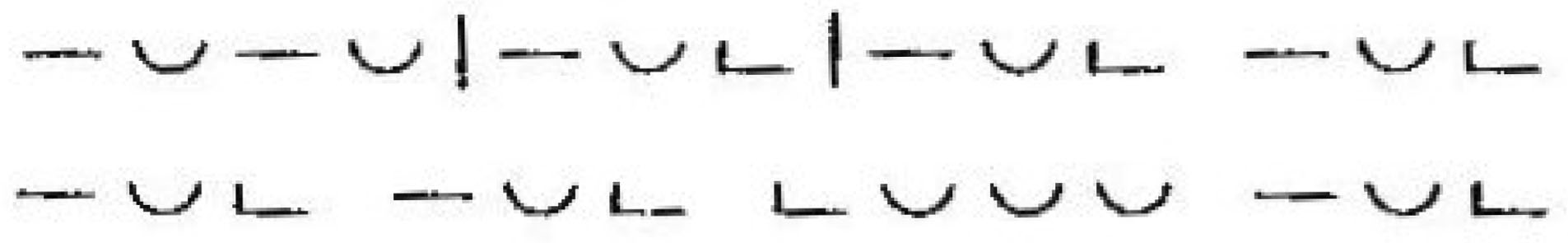

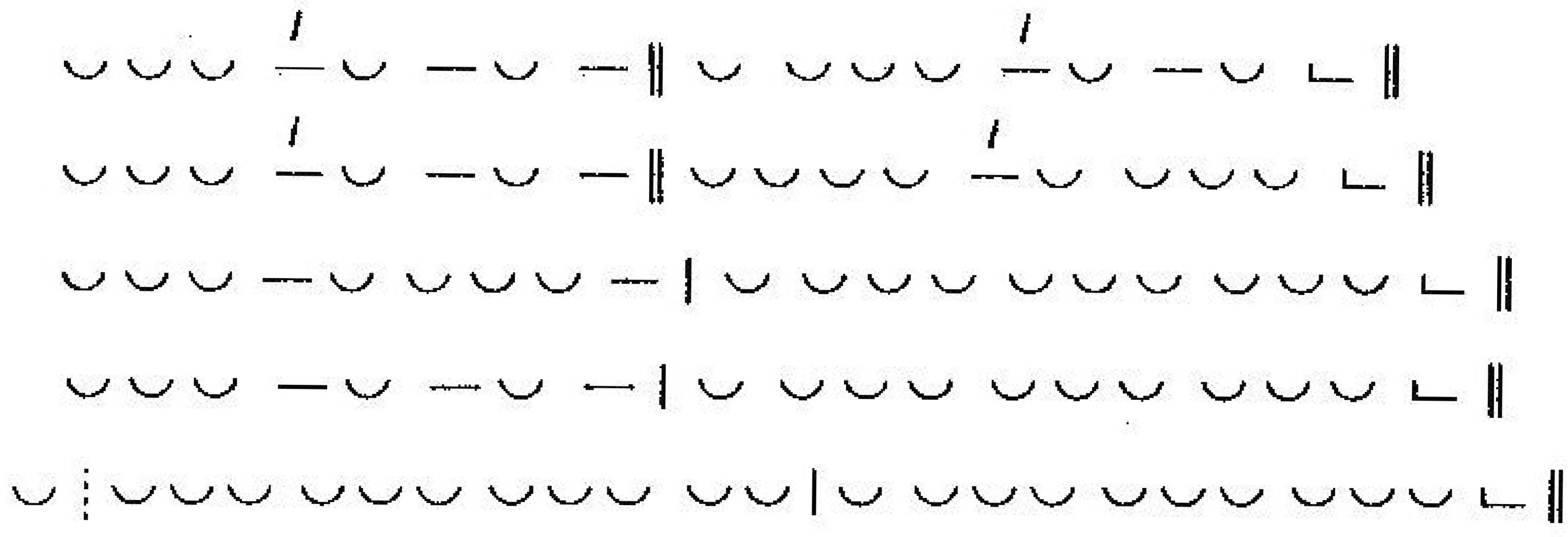

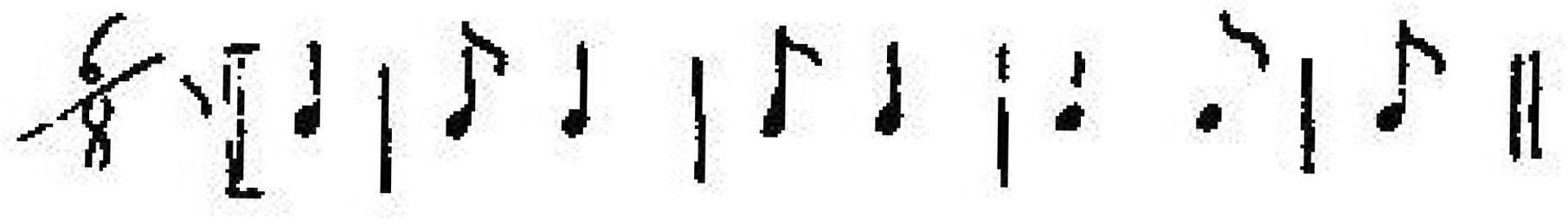

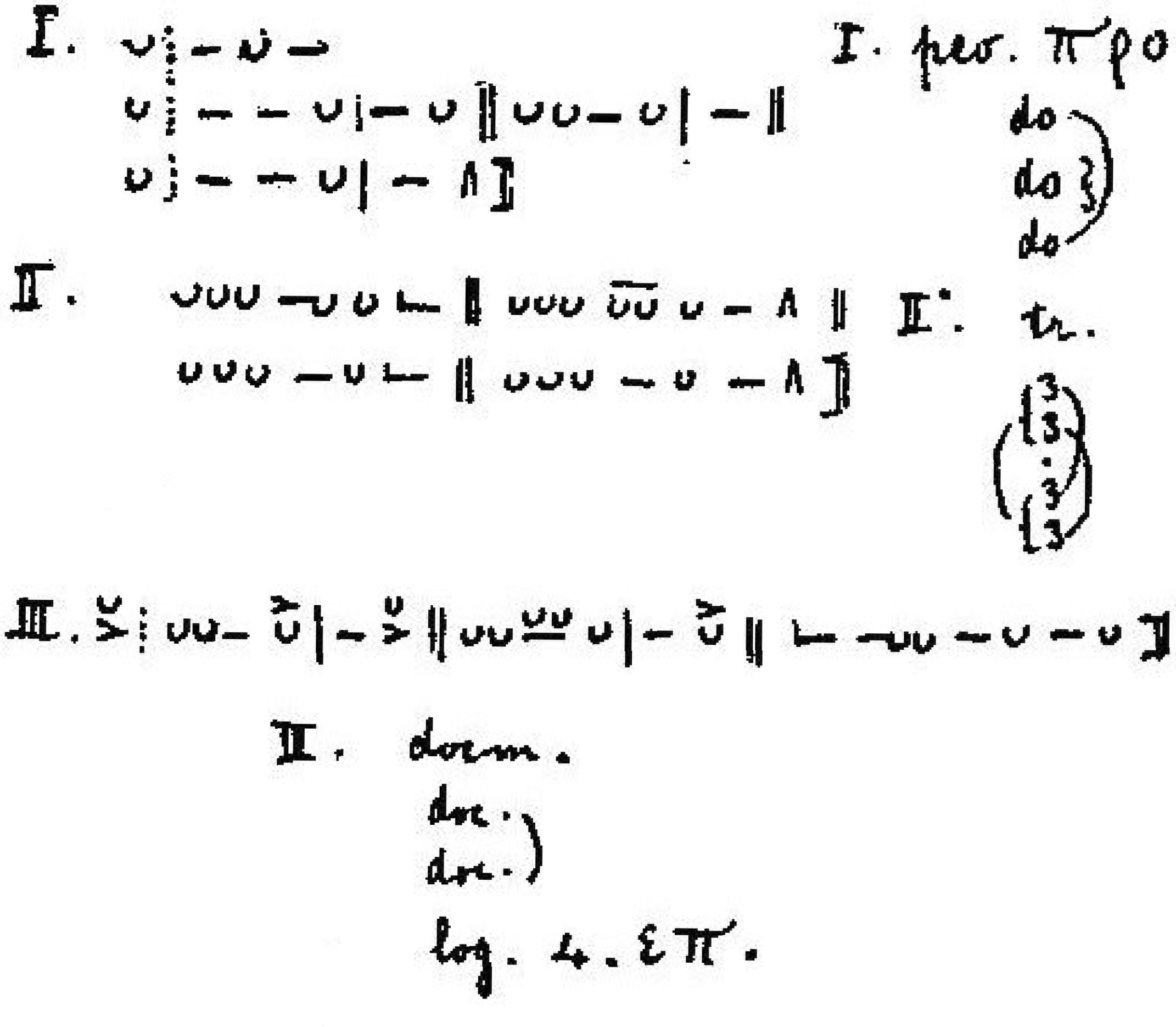

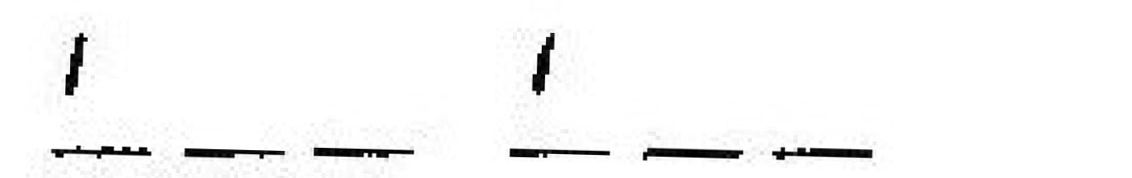

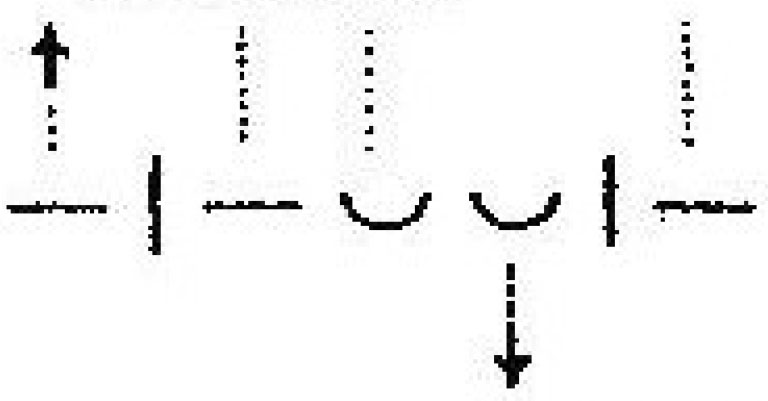

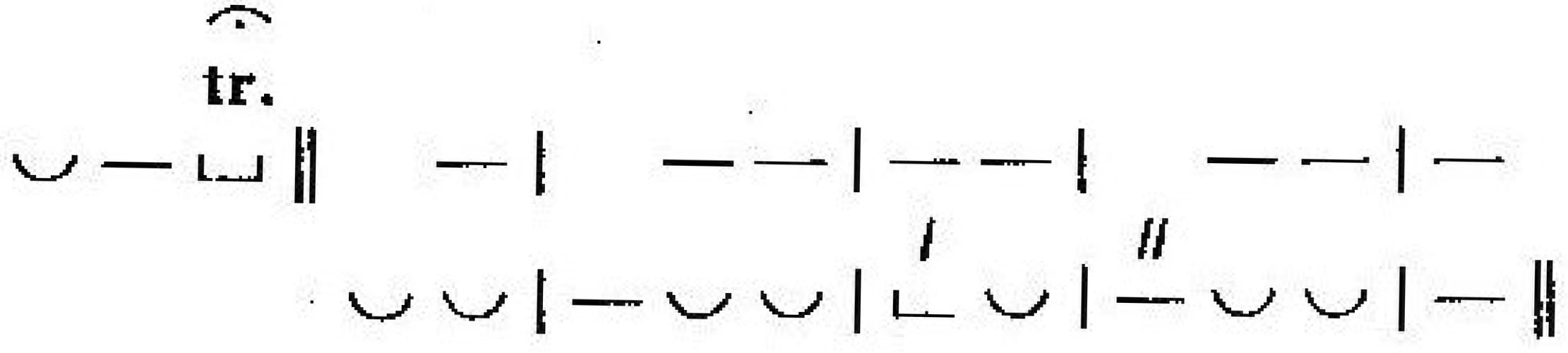

First line of The Iliad:

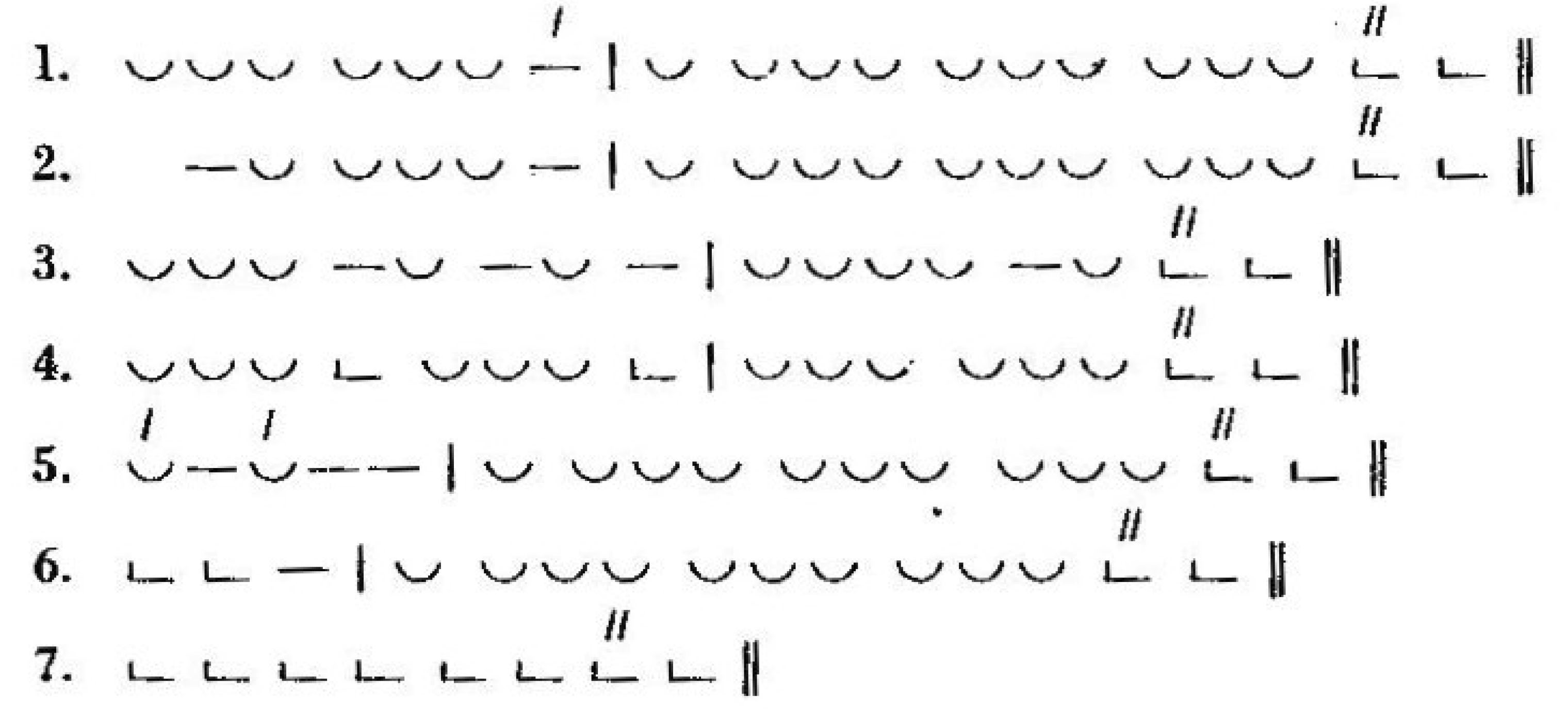

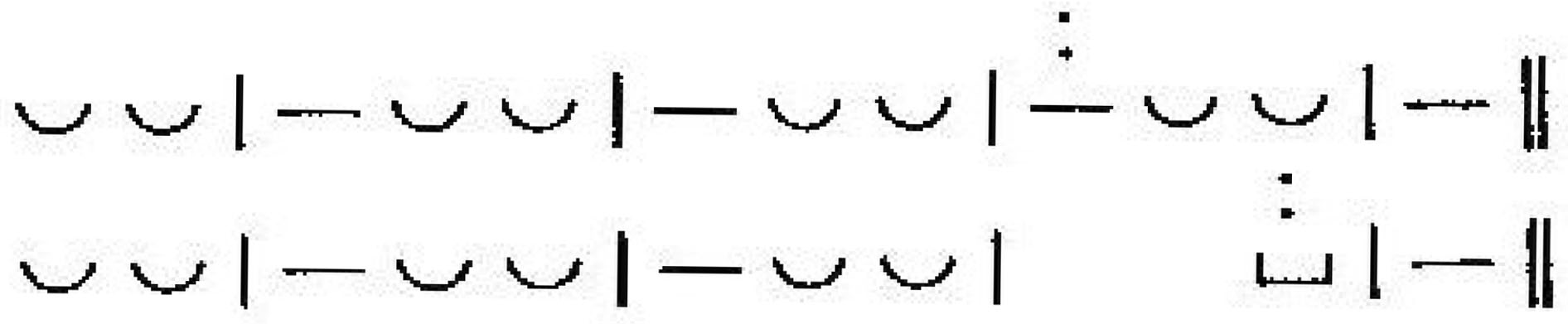

But our scholars and musicians never set foot outside the library, and we need to look amongst the common people to find someone who knows where this old rhythm is hiding, someone who can draw it forth from the smithy into the open air: our tammarinu players. These are the pupils who have learnt from the smiths: “Comu nuatrìri sintiamu li mastri firrara, la sturiavamu supra la tammurinu” [We adapted what we heard from the master smiths and played it on our drums]. The passage is found at the core of Palermo’s Solemn Procession motif:

(the series is continually repeated). I was given this motif by Giuseppe Cacicia, who is more than eighty years old and comes from a family of tammurinàra [drum players], where traditional rhythms have been handed down from father to son for generations. The need for rhythm passes from work on the anvil to work on the drum, where the same law is applied to different materials. The tammurinàra has rhythm in his blood and sinews, while for the rest of us, it has become something abstract. It only takes shape in the malleable substance of musical sounds, which are not bound by any laws of tempo.

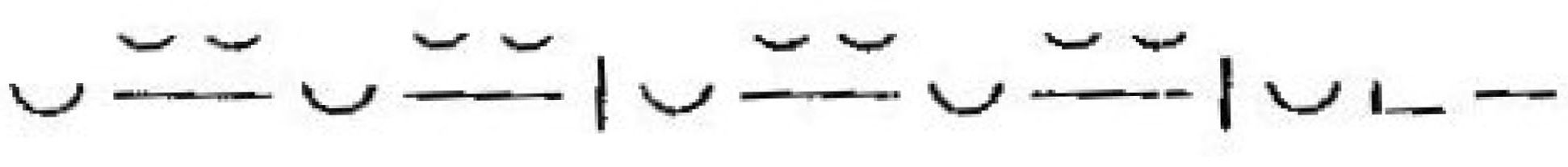

Palermo’s Solemn Procession actually offers us a Greek prosodion, which is exactly the same as the primitive example that has survived in the Spartan folk song in honour of Lysander:

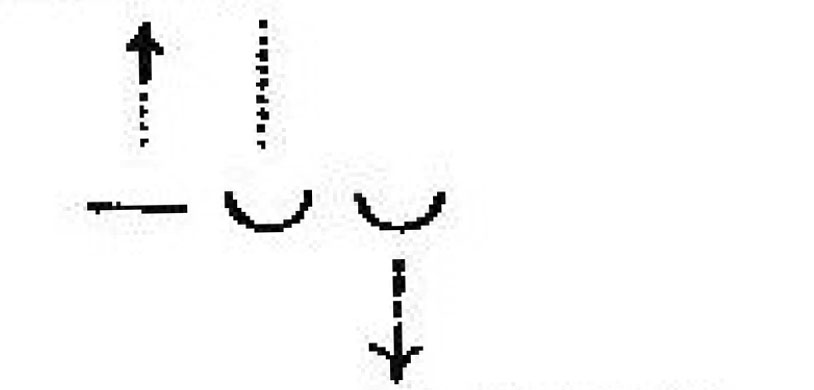

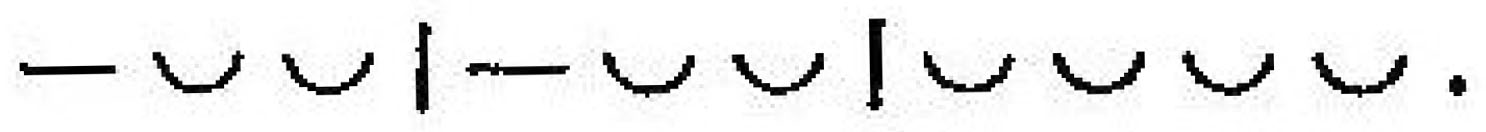

This relationship and identity between the form and use of Sicily’s popular rhythms and those of classical antiquity continue to persist in all genres and species. With the abbanniatina di la tunnina [sing-song calls of the tuna streetvendors], Cacicia gave me another example of a quick march, similar to the embaterion and Tyrtaeus’ anapestic tetrameter. This abbanniatina accompanied the tuna as they were transported from the beach to the town. The arrival of this cheap and sweet-flavoured fish was a moment of great joy for the local people; the tuna was adorned with garlands of carnations and hoisted onto the shoulders of two men. However, the key figure in this ceremony was the tammurinàru because he provided the rhythm behind the march, transforming it into a ritual. At the right moment, the men carrying the tuna used to call out to Cacicia: “Vossa sona, zu’ Peppi!” [Please play for us, Uncle Giuseppe]. While they lift the tuna, the tammarinu starts with an iamb, which acts like a shock and accompanies the initial effort needed to pass from stillness to movement; this is followed by a series of lively spondees, with the preparatory movements that set the tempo of the march, and finally, we have the lively anapestic march, performed in short steps due to the heavy weight that is being carried:

This essential measure is an acatalectic anapestic dimeter; the natural unity of the double step marching (left foot/ right foot) is expressed in the accent on the second unit; the main accent comes in the following unit, marked by a powerful drum roll. The shortness of the meter corresponds to the quick but difficult march, and therefore to the need to invigorate the bearers.

In fact, the same conditions produced the same tempo typical of the armed marches of the ancient Spartans. As they marched to defend themselves, the tribes soon realized that they needed to find a collective rhythm, which transformed a wild horde into a living organism, under a single direction. This spontaneously gave rise to the paremiac, the rhythm of the road, which is an acatalectic anapestic dimeter (metrum laconium messeniacum):

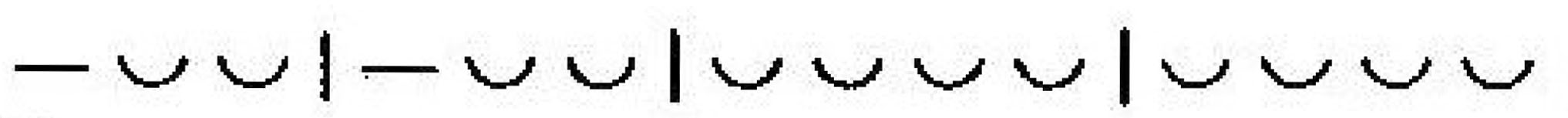

Tyrtaeus found these features in the traditions of the people, as a result of their instincts and feelings. He respected them and transfused them into his ardent poetry, with the delicate aesthetic sense of an ancient Greek, for whom art is always deeply rooted in the people’s soul and customs. The anvil continues to offer us doubletime rhythms when the smith and two apprentices work together: hammer, sledgehammer, and medium-sized hammer.

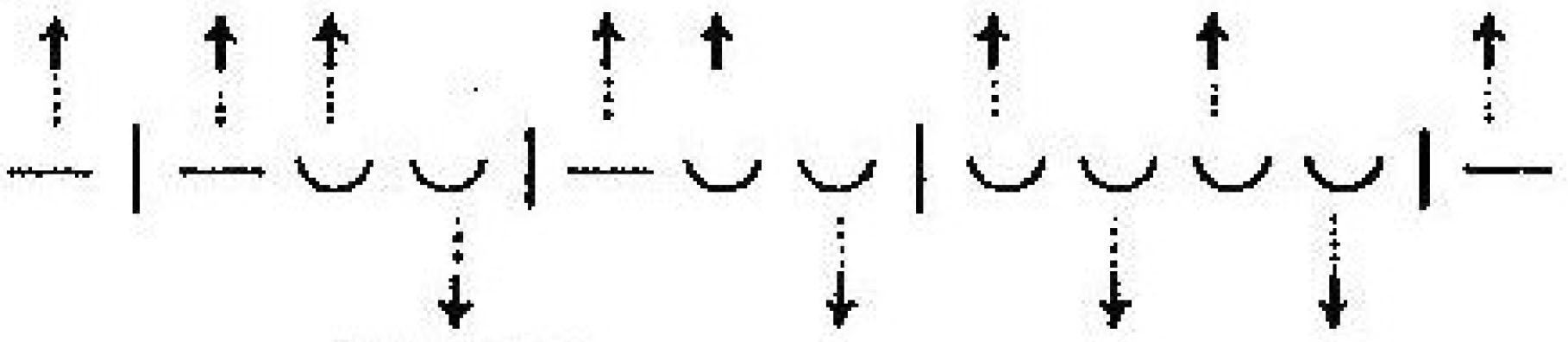

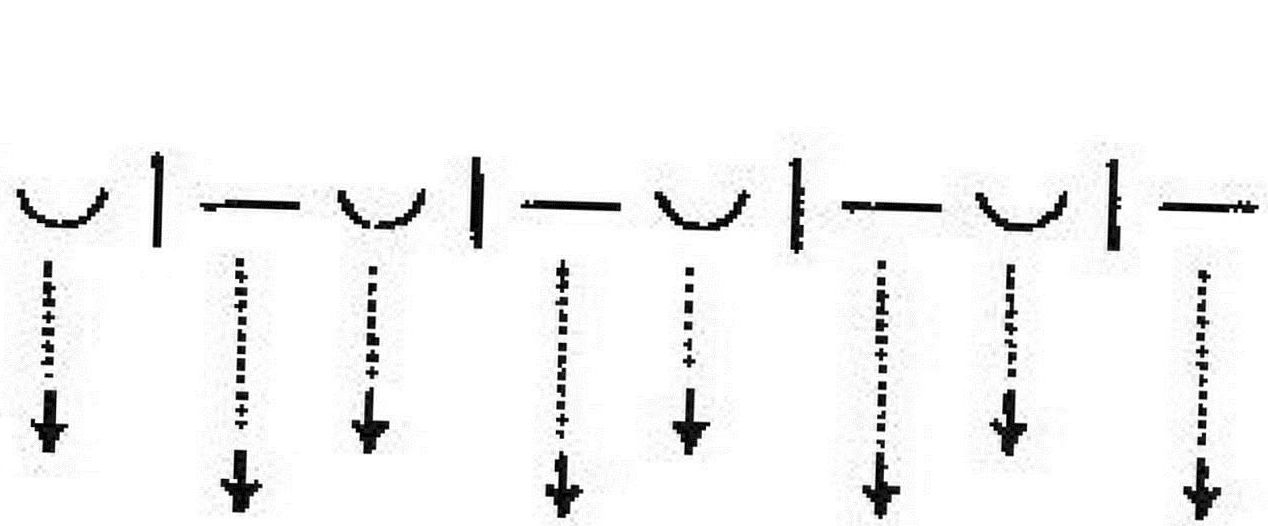

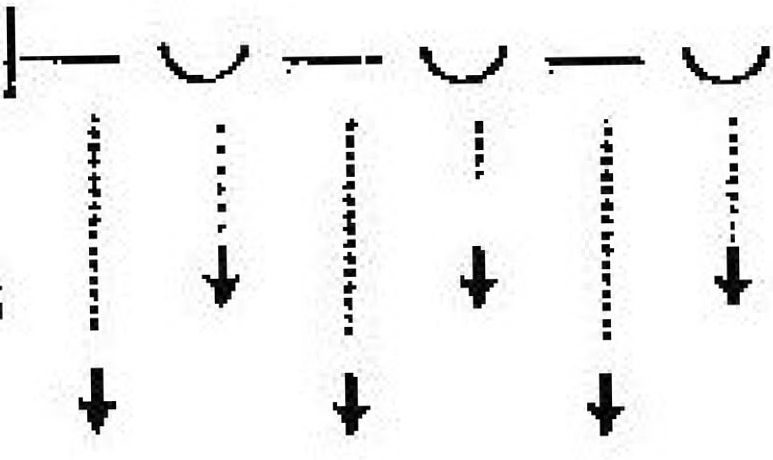

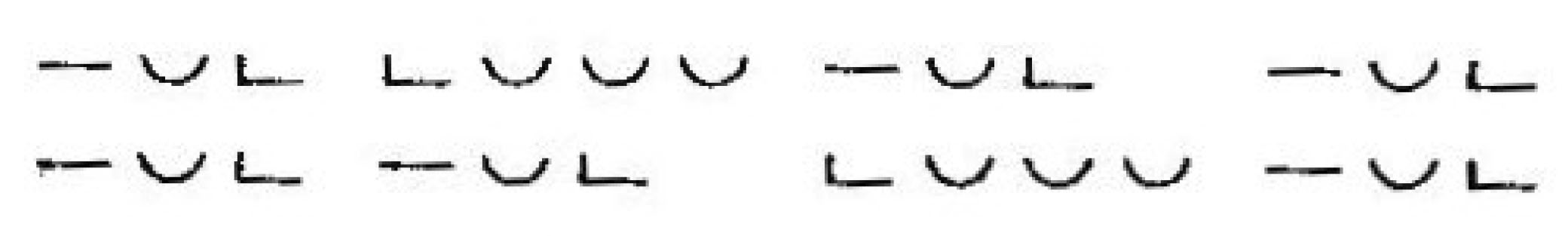

This results in odd rhythms with the most common being the iamb. After the usual preparatory movements to establish the unity and speed of the working rhythm, the three workers take it in turns to strike the anvil:

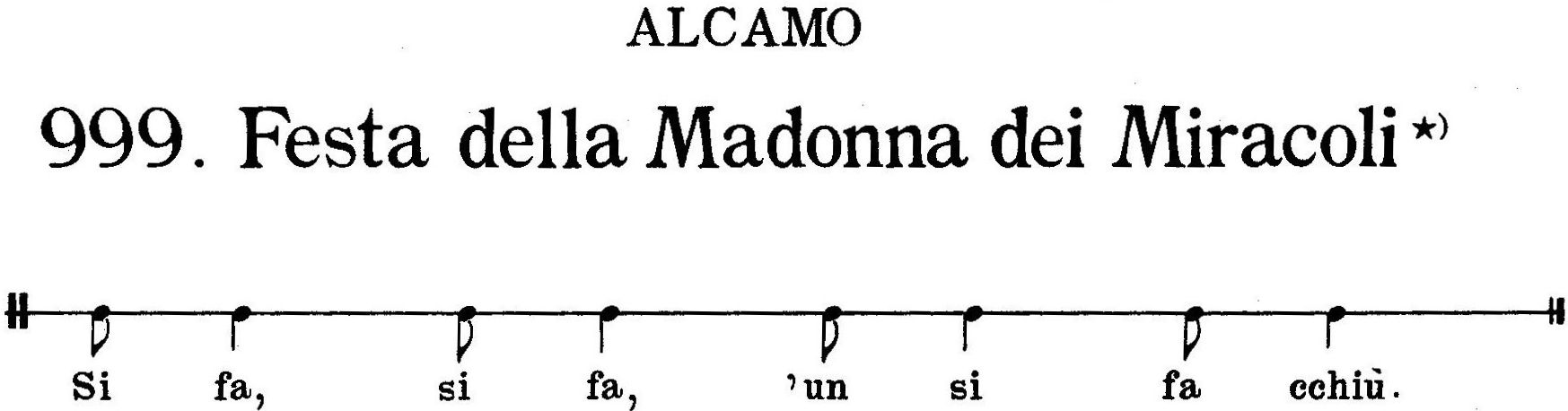

Here the iamb appears in its original function of attacking someone or something. We find it again in Alcamo, in an acatalectic dimeter, which announces a feast that has been put off several times, and where the local people tease the organizers by crying out to the beat of the tammurinu:

“Lu tammurinu, quannu suona, è come fussi che parla” [The drum as it plays is like these people talking]. In fact, it has a certain number of high and low inflections (“lu tammurinu fa l’avutu e lu vasciu” [the drum plays the high and the low]) depending on where the skin is hit; the player alternates these inflections according to a certain criterion for variety and they go to make up a conversation.

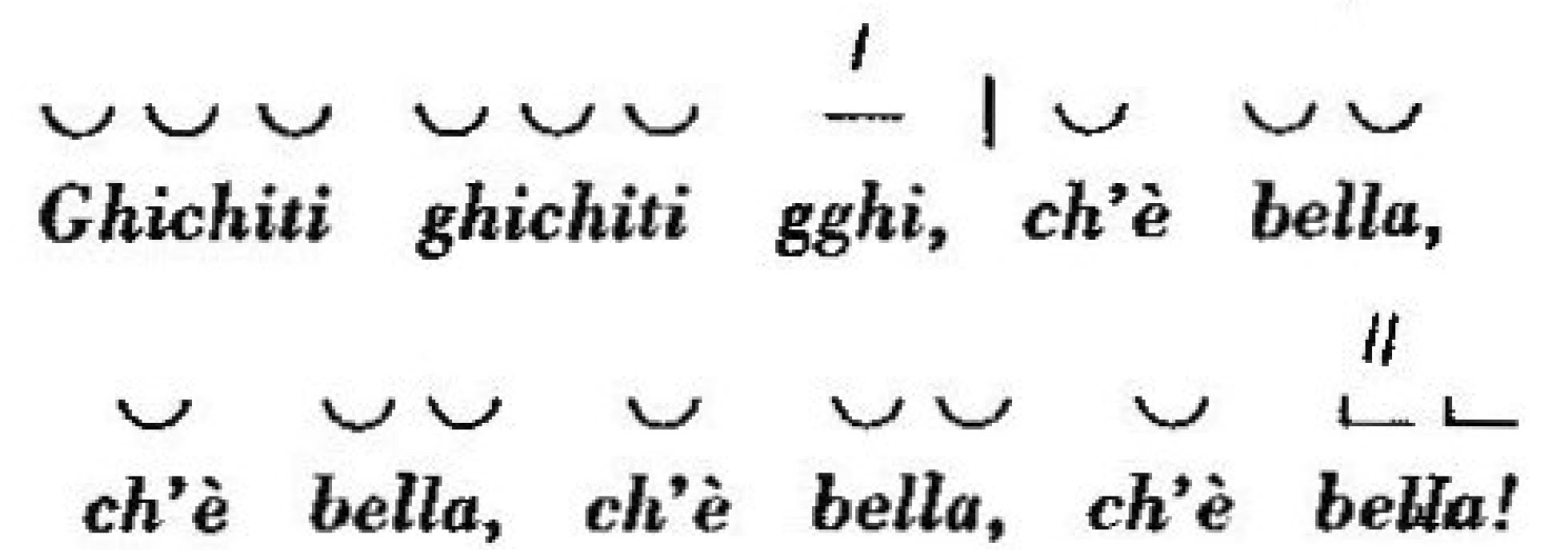

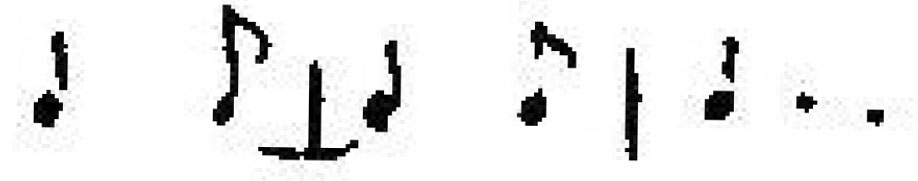

This rhythmic pattern passes spontaneously from the tammurinu and is exteriorized in the dialect. It starts with onomatopoeia:

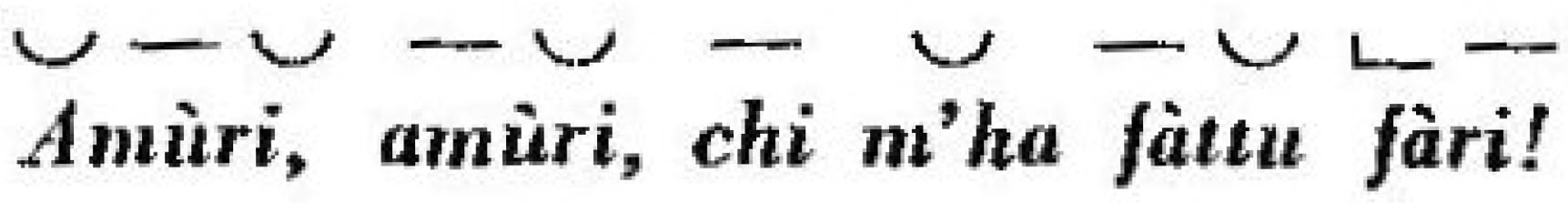

Therefore, the metric patterns of our popular poetry are found in percussion instruments. This is quantitative versification and is not based on stress or syllables, and should therefore be called a brachi-catalectic iambic trimeter and not a hendecasyllable, a word that has absolutely no rhythmic meaning. The number of syllables can increase or decrease in the presence of a tribacchus or a three-beat longa, where the rhythm pattern remains intact:

In this line the stress of the words coincides with the rhythm:

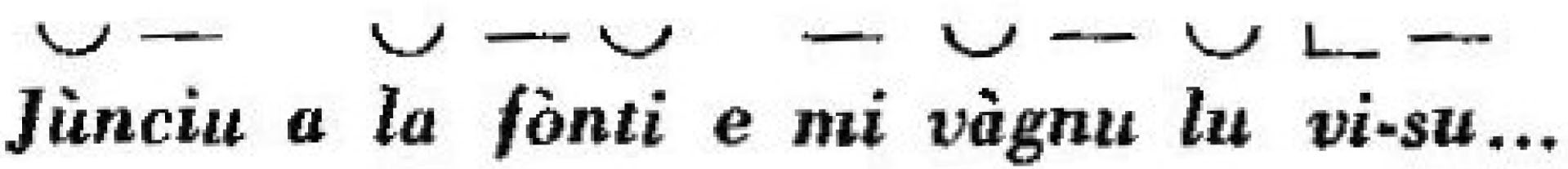

But far more interesting is the application of the iamb to our body movements. I found that my 5-year-old daughter Teresa unconsciously produced an iamb as she hops-skips-jumps forwards:

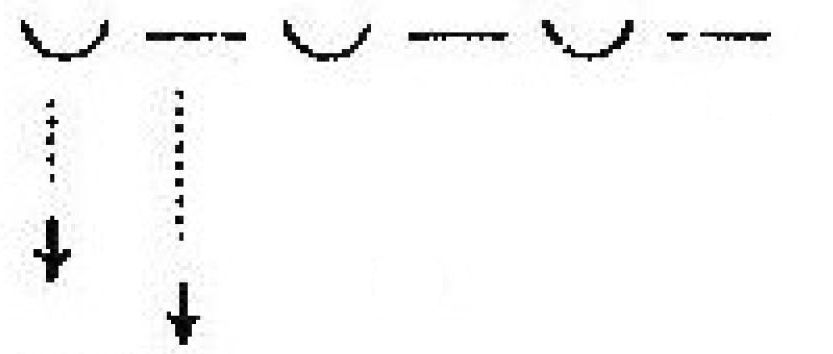

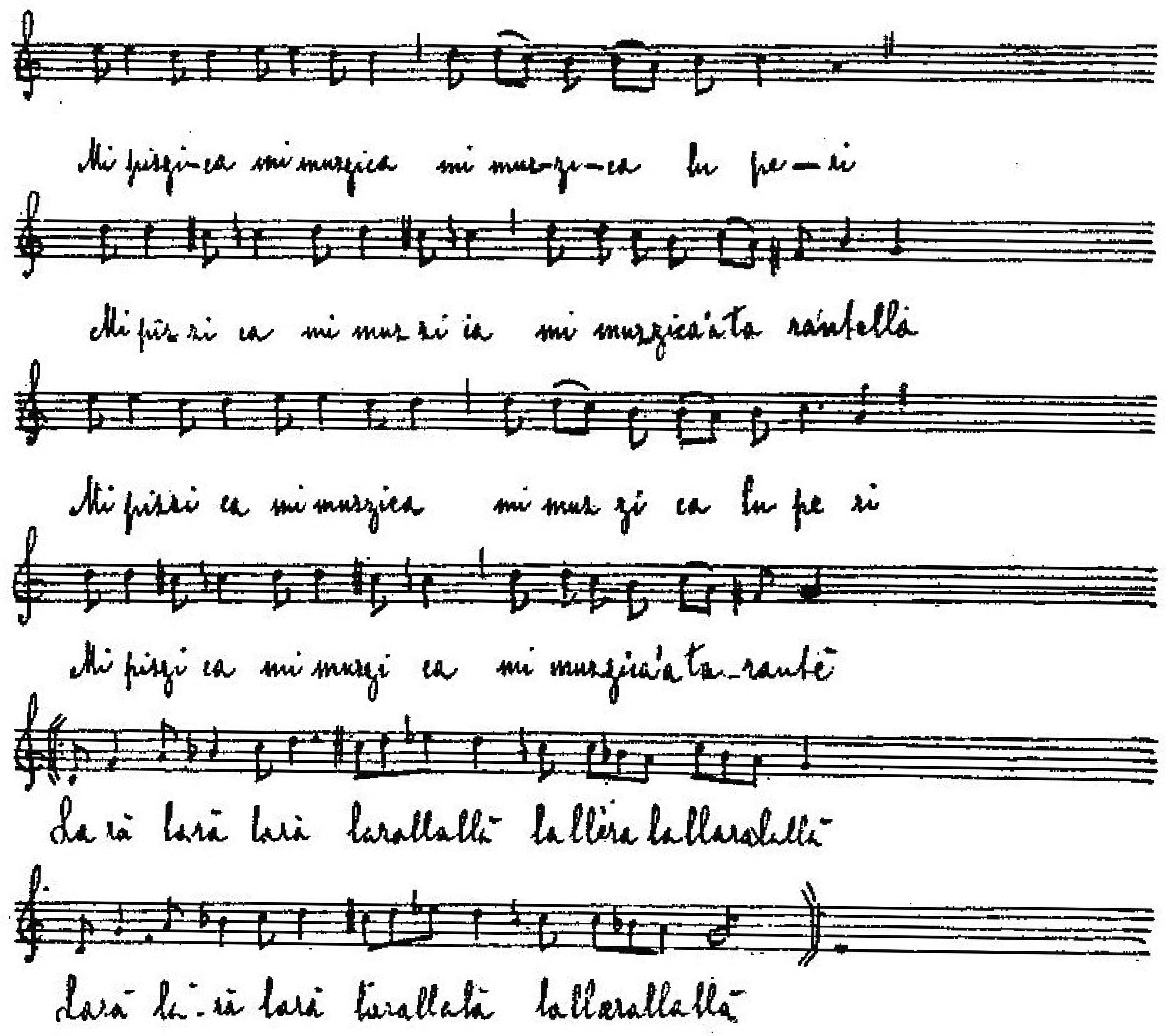

She starts off on her left foot and then lands on her right. Another malleable form of iamb is found in the traditional dance for women called the “Mi pizzica, mi muzzica” [he pinches me, he bites me], in which the dancer hops up and down on the toes of her left foot. The arsis indicates the hop into the air, while the thesis is the landing.

But some other lines read:

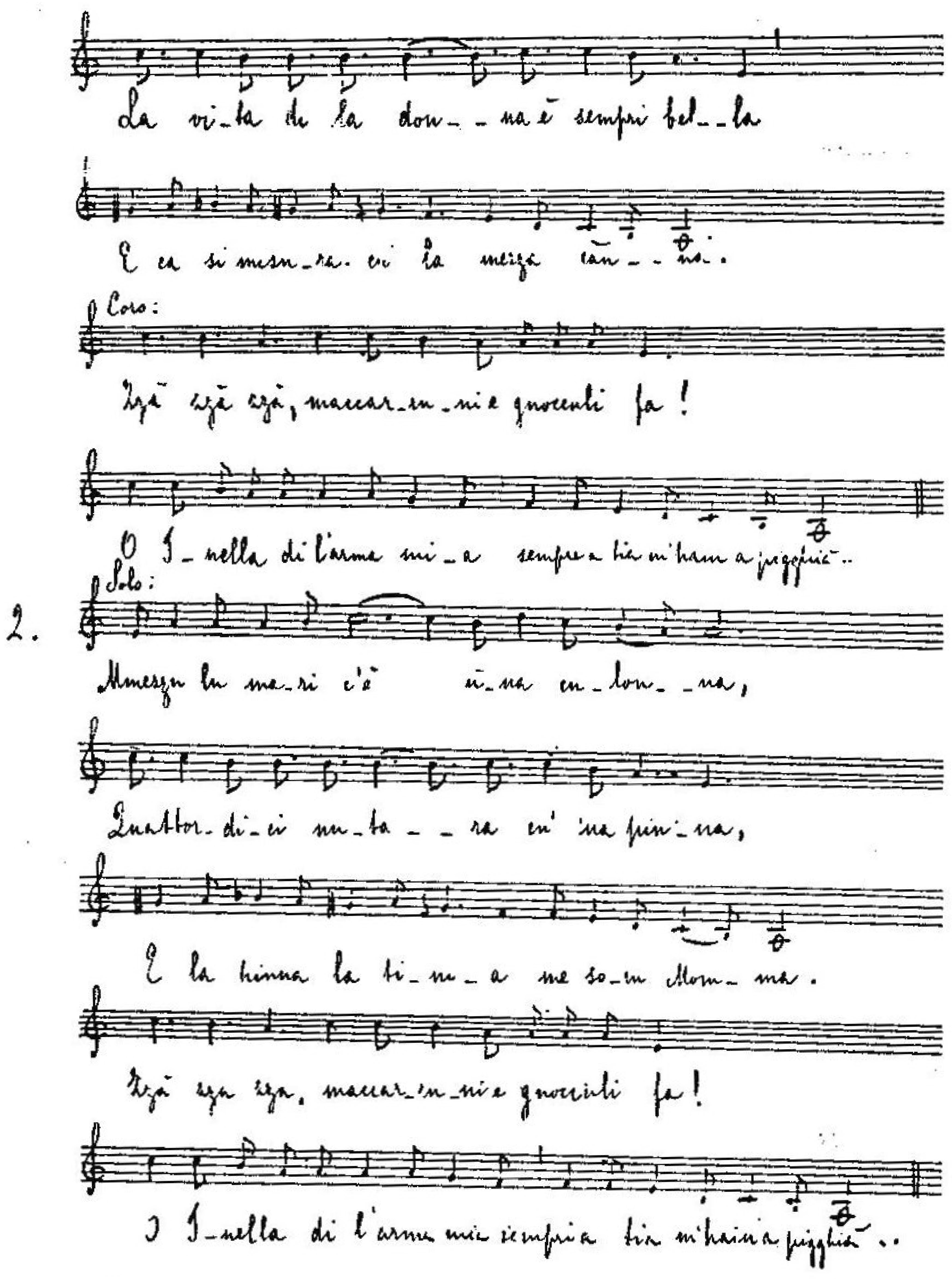

So Bacchus’s brew had something to do with it! Basically, there was an explosion of all the pent-up energy that people had accumulated during the repressive Mediaeval period. A state of exuberance in life exists where the health of each individual is confused with disease. But this state is actually beneficial for the species: it is like a river that overflows its banks and destroys everything, but which, as soon as it returns to normal, leaves behind lands that are fertile for centuries to come. In fact, these are the periods when humanity revitalizes itself. The Homeric culture in Greece was preceded by such an obsession, and the Renaissance in Italy comes from tarantism, more than from humanism. Every population has suffered from these diseases where normal life is transformed into a cruel and relentless orgy: the Greek bacchanalia is a stylized example. And the iamb is precisely the rhythm of this state, which not only influences the motifs of the body, but also those of the spirit and its common and risqué songs. Here is an iambic song from Palermo:

This is an iambic way of seeing life, in a land that is filled with contrasts: pain is overcome with irony and scorn; the absurdity of everything, found in the imperturbability of universal life and the accidentality of individual life, is grasped and then laughed about, and the plebeian laughter burns and cures. This was how the goddess Demeter forgot her sorrows, when Iambe, her servant, sang and danced before her – probably in the iambic meter that takes her name – and made the goddess roar with laughter. The secret of the iamb lies right here in Demeter’s laughter which, as if by magic, manages to lift the goddess’s spirit and erase the memory of the Titans’ atrocious violence. Even Aristophanes laughed in iambs to get over the Hellenic decadence; in Frogs, he maintains the boisterous song from the goddess’s popular cult: “O Demeter, protect my aged knees with laughter, jokes, and serious proposals”.

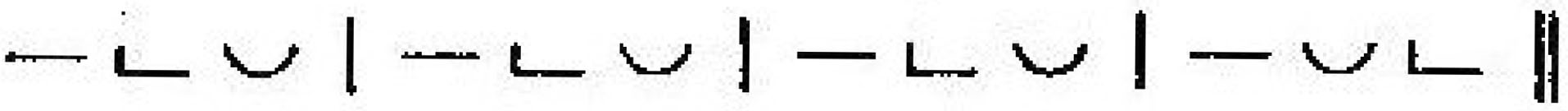

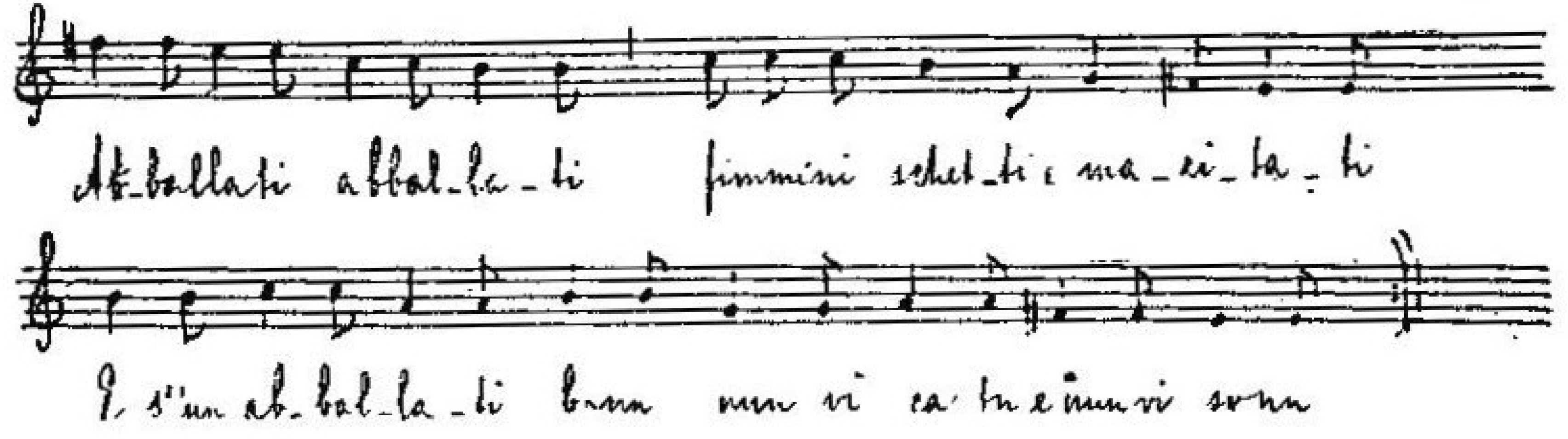

Another purely trochaic sung dance is the following from Palermo:

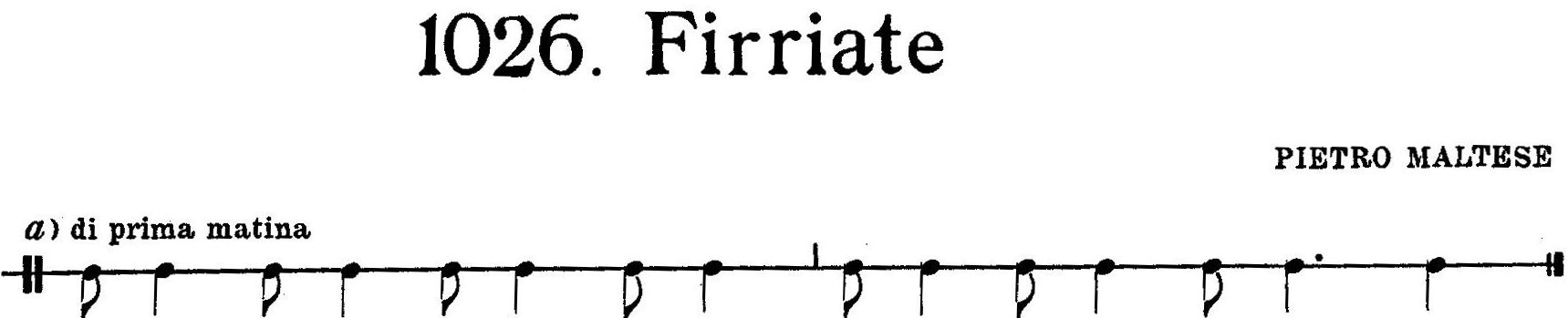

I found the same form with the tammurinu in fast-moving processions, when the candles dedicated to male and female saints are carried to the church:

But this is no longer the trochee of the circle dance: it has a different form and is the choreus, that is to say, a very quick march. In fact, the tammurinàra have this to say about this composition: “E’linusa, ci voli lena assai, si curri” [It’s quick, you need to make good time, you run].

Even the choreus is interspersed with light tribacchuses, as in the trochee:

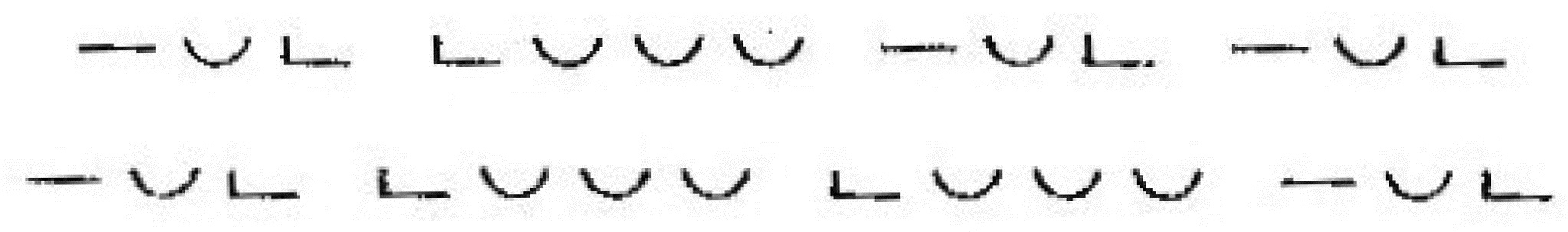

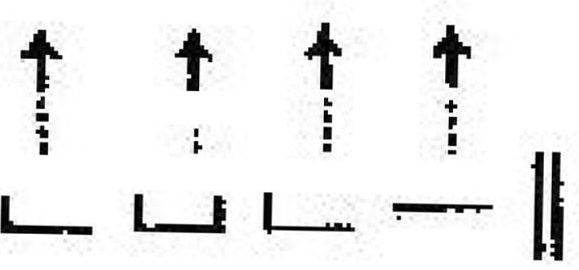

The primitive form of the cretic is a dipody, made up of a choreus and a three-beat longa:

So what exactly is the cretic mode? The longa indicates the falling movement of the body, an energetic cadence after the light impetus of the choreus. Now, I have gleaned this orchestic form from my knowledge on the spontaneous production of rhythm. My seven-year-old daughter Anna often expresses her childhood feelings by jumping and dancing; her well-proportioned body unconsciously follows the laws of rhythm, in such a way that her emotions are transformed into different patterns of regular undulations. She often repeats this pattern as she runs forward:

This is certainly an example of a cretic form, but can we say that it is the cretic of our ancestors? Of course, nobody can say this for certain, although it is definitely a tempting hypothesis, which has much in agreement with that nocturnal image, left to us by the poets, of a chorus of satyrs celebrating and skipping forward as they perform their danced prosodion.

This interpretation of the cretic, mainly based on the living experimental fact of a dancing child, is therefore unquestionable, but actually in contrast with the ancient doctrine of the Alexandrine meter, where every longa is reduced to two first beats. Something similar has come about in the interpretation of elegiac verse, where we modern folk have reduced the pentameter to its correct length with the four-beat longa; we have done the same with the cretic and the paeon, lengthening the two-beat longa to a three-beat one. Callisius conserves the melos creticon model in Fragment 222, the ancient dance melody from Jupiter’s holy island.

With Talete, the paeon-cretic moved on from Sparta and became part of the gymnopaedia and art. Here the basic form was amalgamated with other double rhythmic forms. Attic comedy conserves the first examples of this process of differentiation, adding the fourth paeon (

These three first paeons and a cretic are the typical form used by Aristophanes: here we have a tetrameter that flows and takes off, and the poet composes lively palinodes with trochaic epodes:

The choreuses indicate a slight slowing down in the cretic impulse, in homage to the artistic principle of variation. But a greater modification occurs when this principle is applied not only to the musical rhythm, but also to the extension of the phrase members. This happens in the most advanced Doric chorus and in Aeschylus.

Here, amongst all these trimeters and meters, the sense of eurhythmy passes from the line to the period. The original surge of cretic paeons is transformed into a calm procession, which comes to pass in the evolution of the strophe, the antistrophe, and the epode.

Once the Hellenic culture came to an end, the cretic paeon returned to the grey area of popular life, where it lived on forever, unheeded in the irresistible instinct of the body’s muscles. In fact, I came across it in the San Ciro district near Salemi, produced in exactly the same manner as in ancient times. Far off in the distance in the autumn evening, I heard the uproar of the fiery cretic played by the tammarinu, as their incessant and irresistible drums urged on the torchlit procession in honour of the local saint along the lower slopes of the hills and down into the valley. The rhythm throbbed with all the ancient mystical exaltation of the flames that shine out in the darkness. Every now and then, the crowd shrilly invoked the name of the saint, just like the Sicilian’s primitive god, Dionysus-Zagreus, who loved racing and collective dancing (filocorèuta).

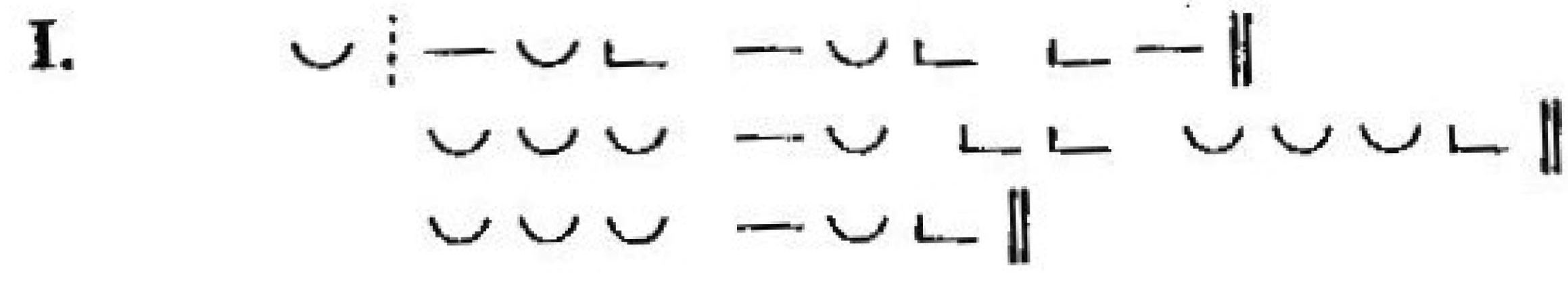

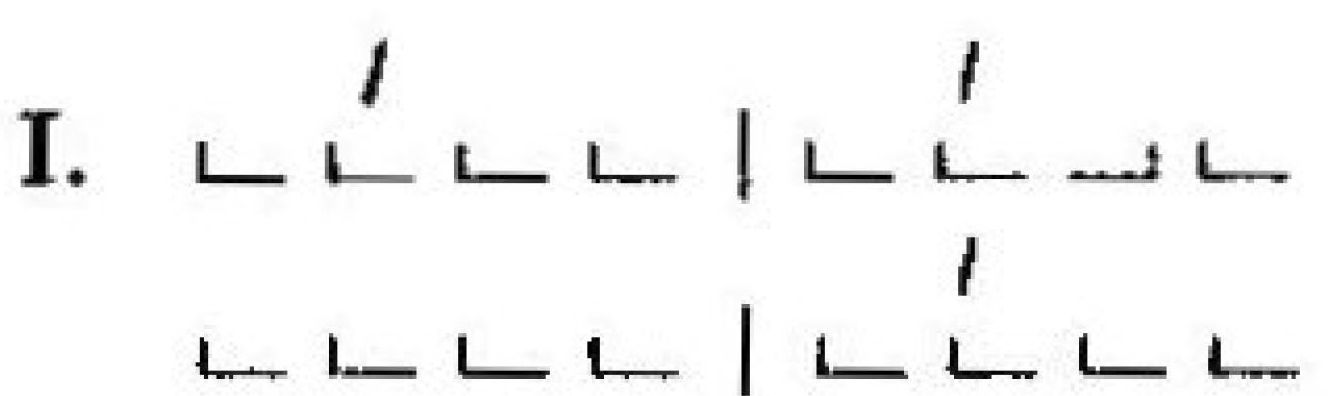

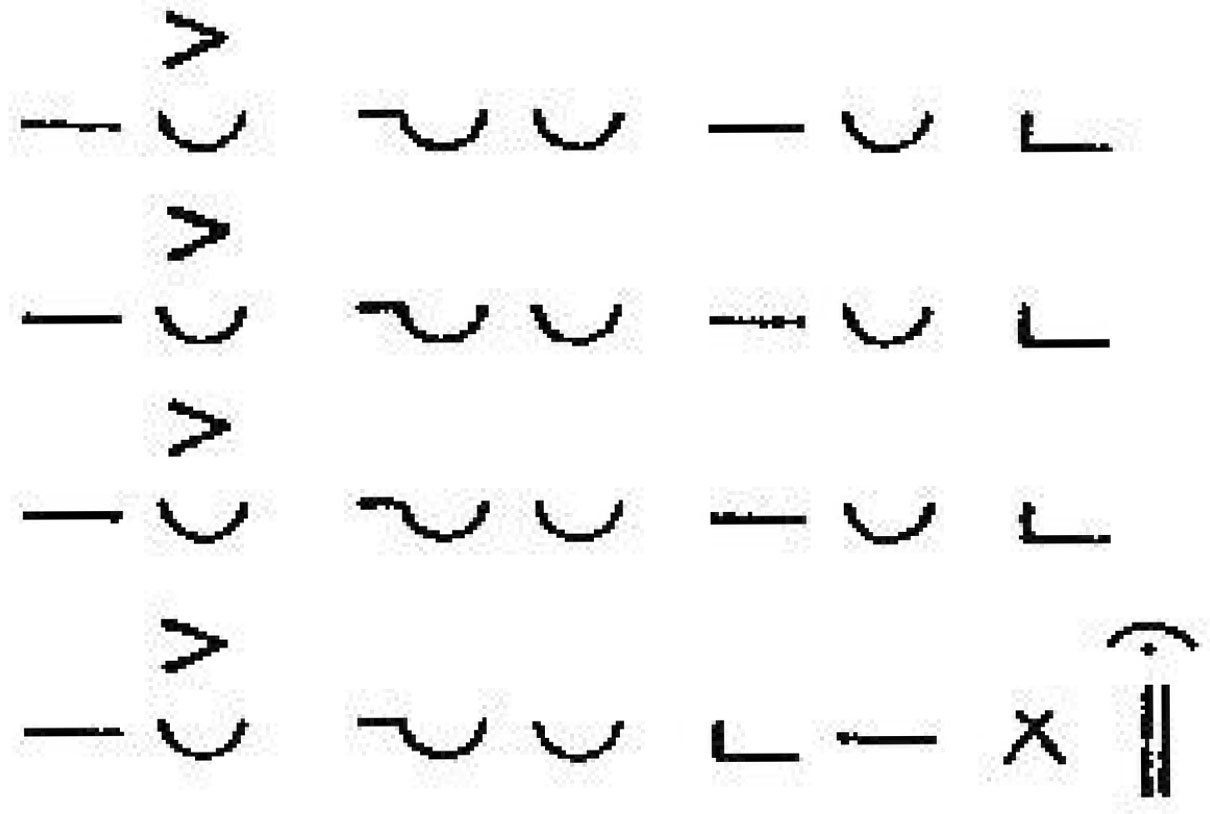

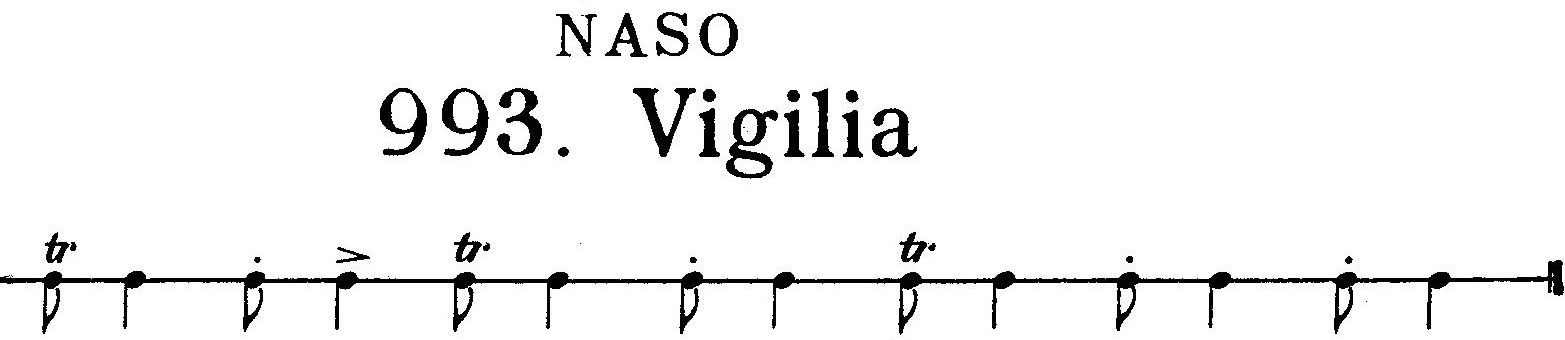

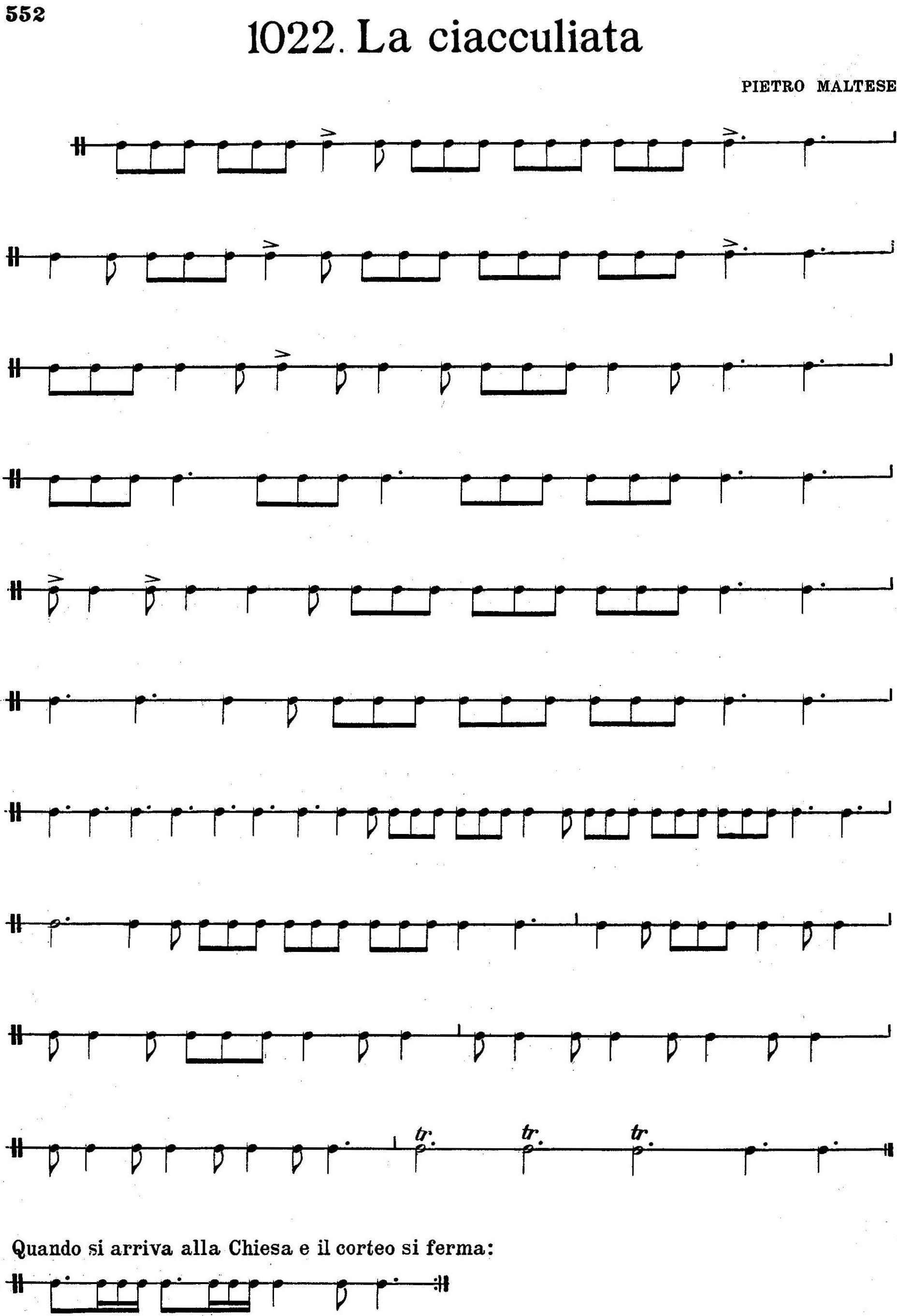

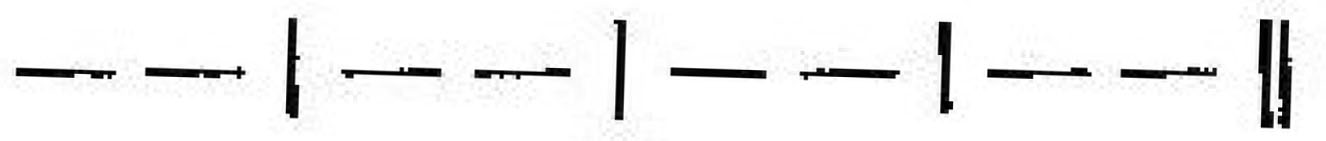

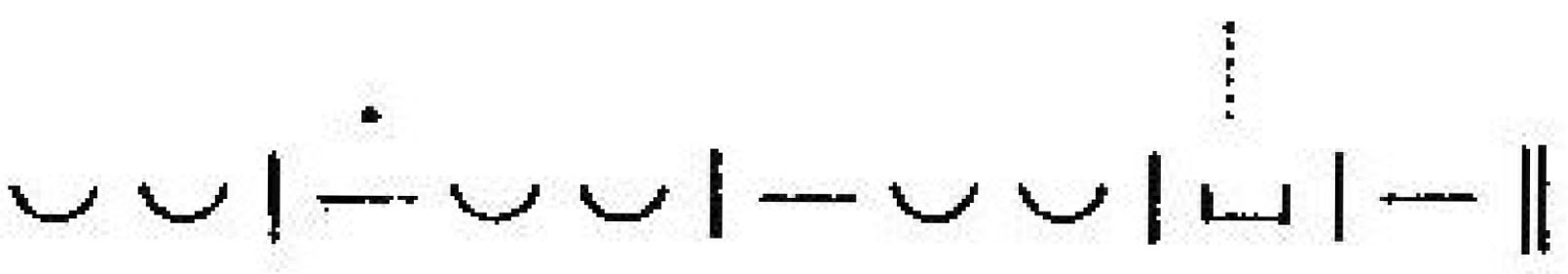

CIACCULATA [5]

I observed that this Ciacculata had a primitive cretic paeon: it had the same virile and passionate nature, the same vigorous and lively orchestic form, and the same wealth of rhythm. It offered a search for contrasts obtained by opposing the various types of rhythm.

Almost all the lines have caesura; in the first dimeter, the line gains momentum, and in the second it precipitates from lively tribacchuses in the brachi-catalectic dipody, with a greater rest in the cretic cadence, in relation to the preceding stress. Line 7 with its three-beat longa is set between lively tribacchuses. The greatest contrast occurs between lines 11 and 12: the former has eight reversed iambs and is a period of pertinacious fury and violent jumps, with no caesuras or cadences, while the next line rests in long six-beat notes. These longae can be found in Fragment 23 of Bacchylides, in a cretic hyporchema. Reversed iambs are found in Pindar’s and Aristophanes’ paeonic compositions, but never in a continuous series, as shown here in line 11. The series of three-beat longae are found again in Aristophanes’ Birds, 1058ff.:

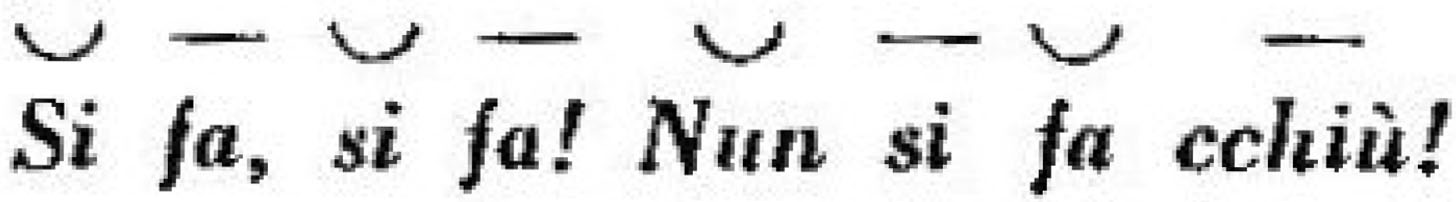

After having wound its way around the countryside, the procession returns and stops in front of the sanctuary. This is where the tammurinaru usually starts off his majestic and solemn trochaic epode, in a catalectic form. Each tammurinu beat usually has its epode, which is always opposite to the previous one, and it conventionally marks the end for the people, just as the ancient epode did in Greek lyric poetry. Our people have these rhythms in their muscles and in their souls and they can feel its suggestive power. They express this ethos in an original way, applying words to the rhythms. Salemi’s Ciacculata says:

The repetition of these words shows all the excitement that this race offers.

In Montalbano Helicon, I found a cretic tetrameter whose words contain all the malleable expression of the movement:

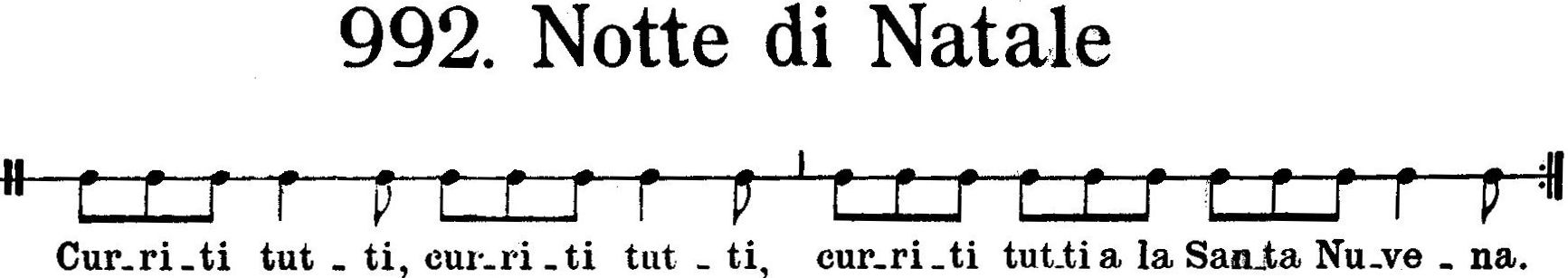

The rhythm of the tammurinu tells the people to hurry to the church to participate in the mysteries of the nativity of Jesus of Nazareth: “Unca lu tammurinu nun parla?” [Why doesn’t the drum speak?]. The acatalectic form with no cadence gives the precise image of the continuous flow of people rushing to the temple. The cretic mode is very common in Sicily and offers a great variety in its musical realization and the extension of the phrase members. Every village, every town has its own form, whose delicate undertones reveal the character of each district and mankind’s exquisite sensibility to rhythm.

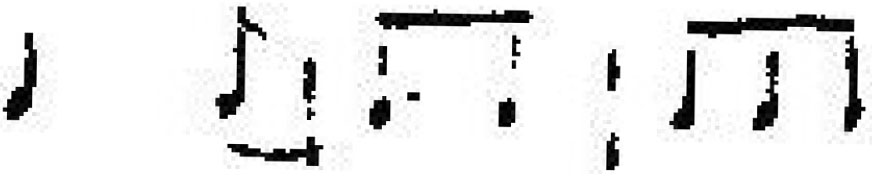

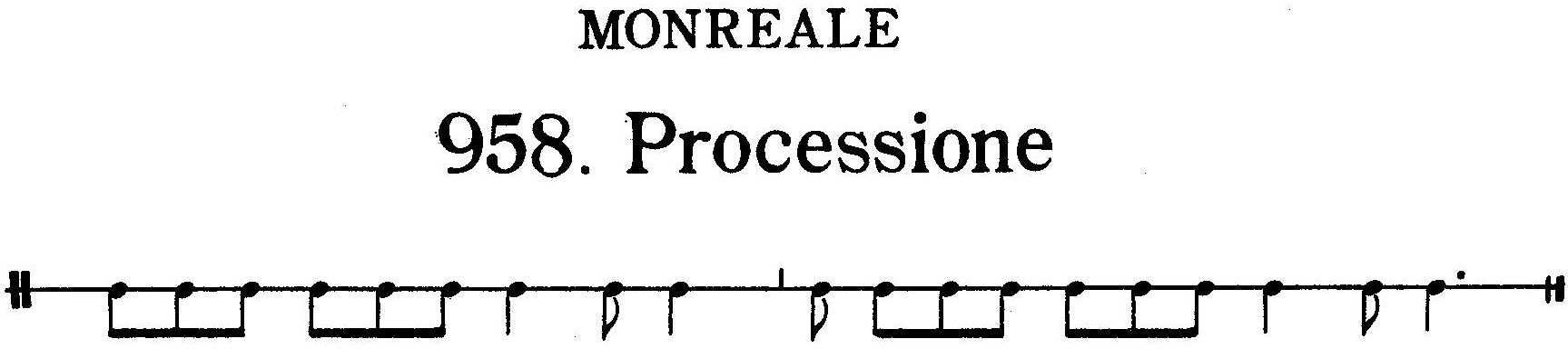

This impetuous motif for processions from Monreale, high up on the Conca d'oro, urges the faithful to dance along:

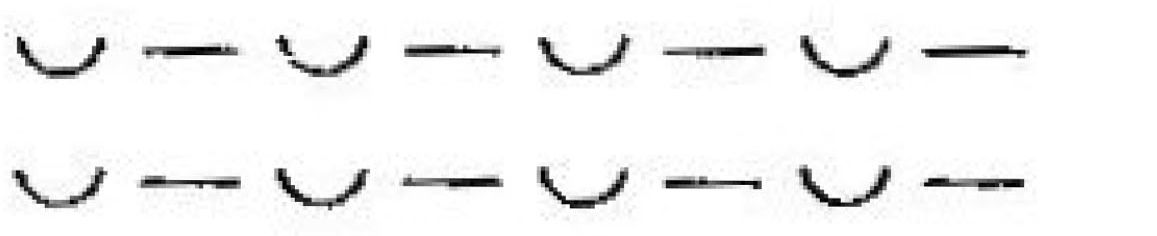

Cinisi, on the plain, has quieter motifs. The cretic is preceded by two perfect choreuses, without any whirling tribacchuses, and the cadence falls on each dimeter, while the tetrameter has a shorter momentum:

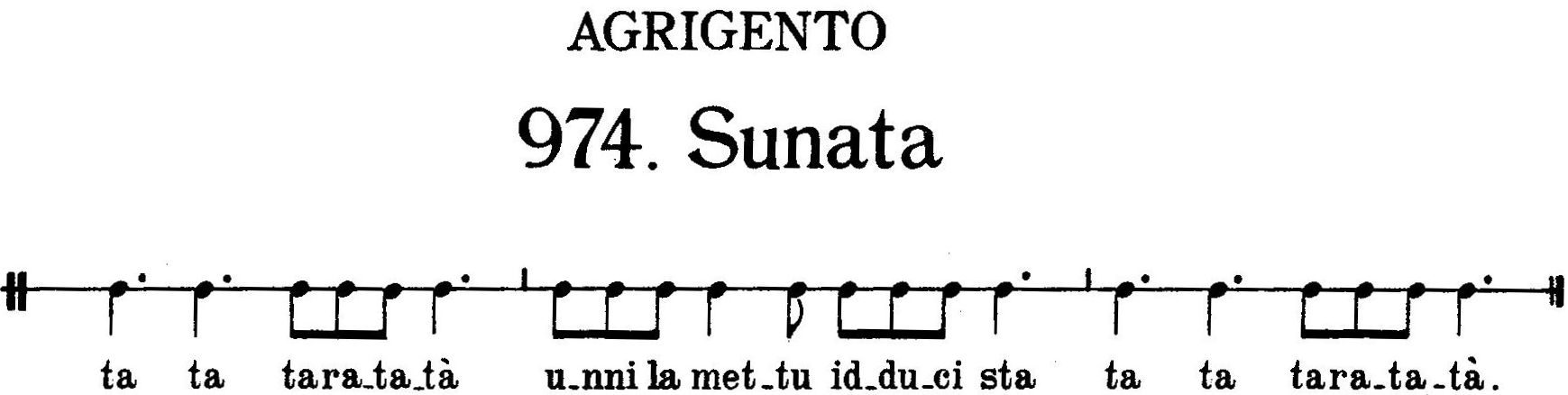

Girgenti has this hexameter which is amazing in its variety and growing momentum:

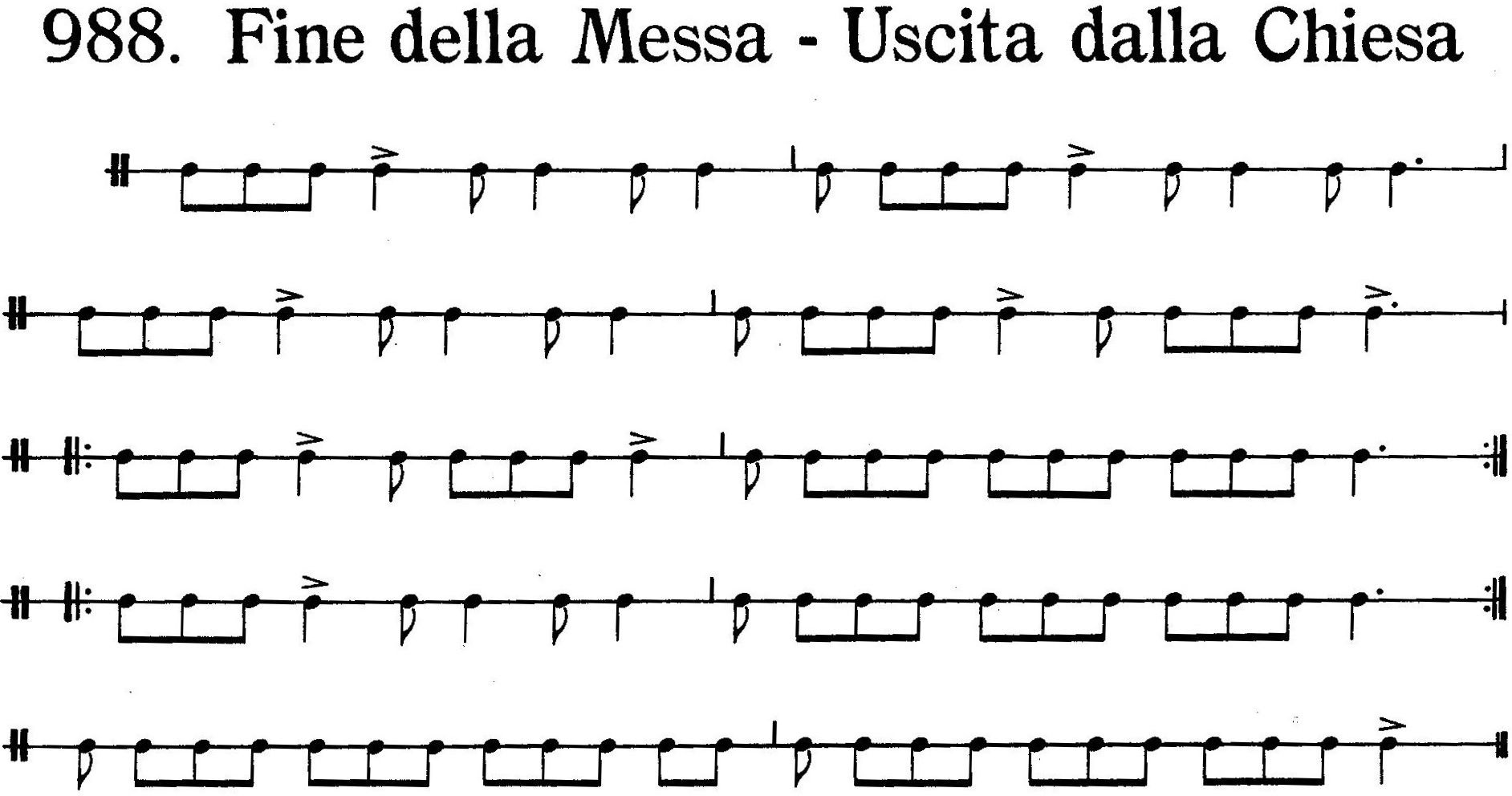

This palinode is played in Villalba (Caltanissetta) as the people leave the church at the end of the Mass[10]:

Everyone returns home in a state of mystic joy, charmed by the rhythm, and the poet sings to his beloved in admiration “Quannu camini pari chi abballi” [When you walk by, it seems you dance]. This is movement in a superior form; the echo of a far-off world, of a full and harmonious life, and our civilization with all its excesses and faults pales in comparison.

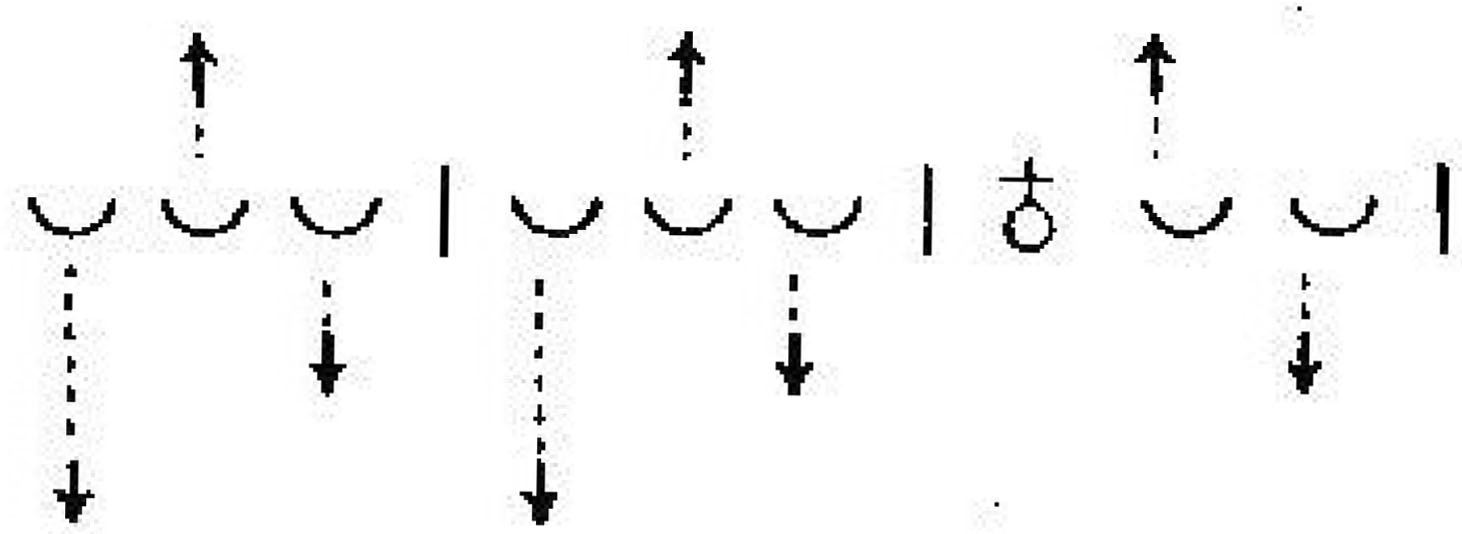

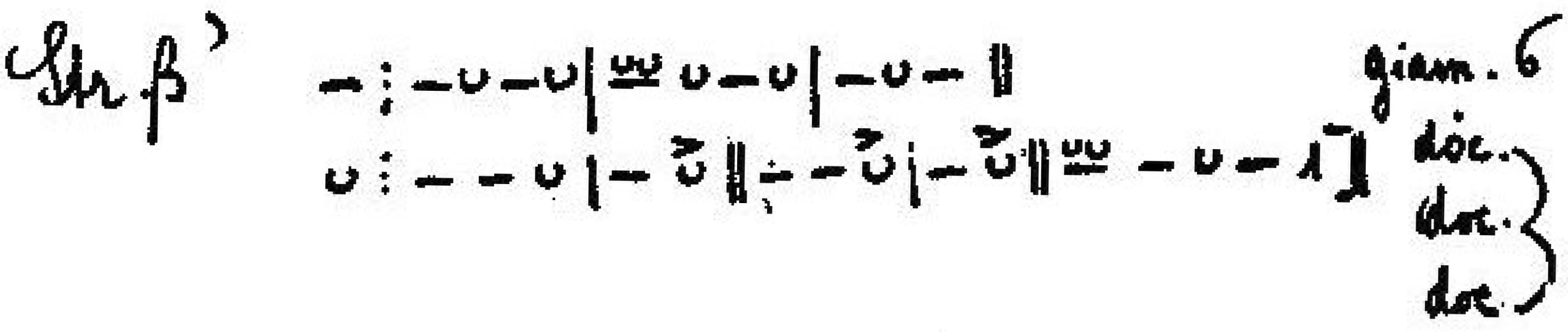

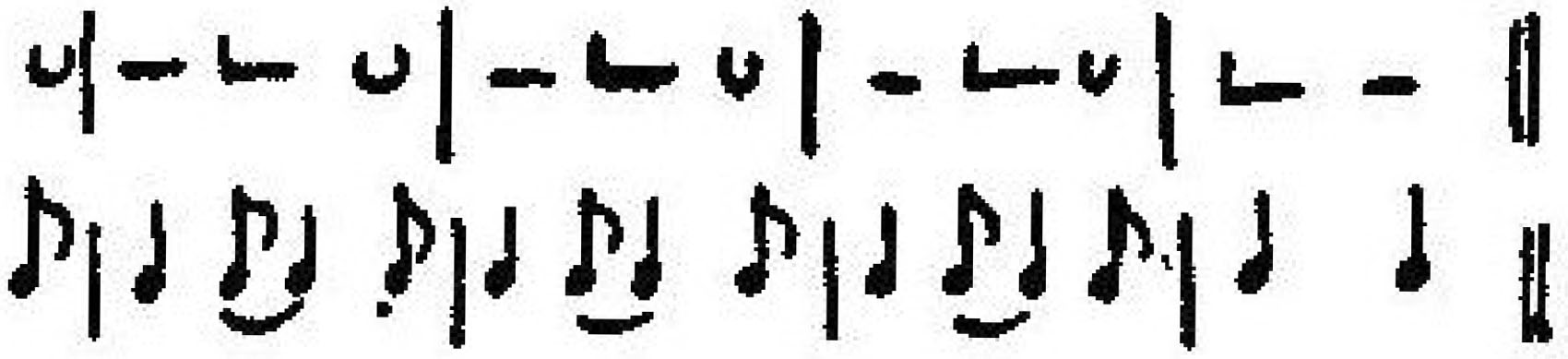

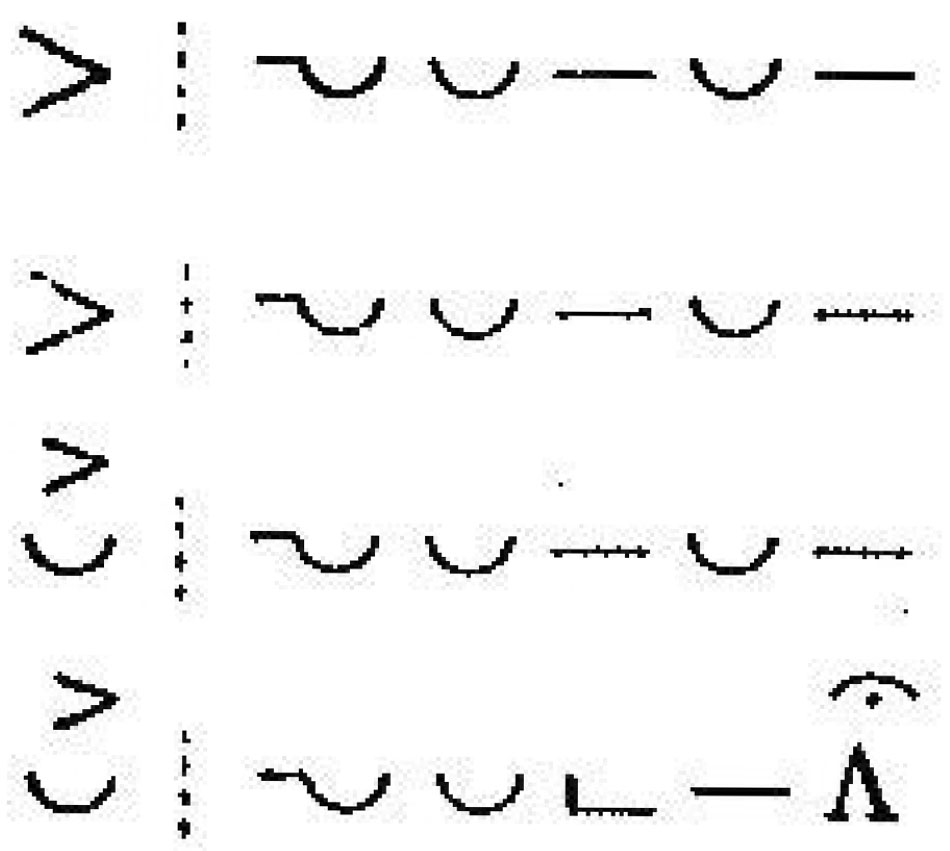

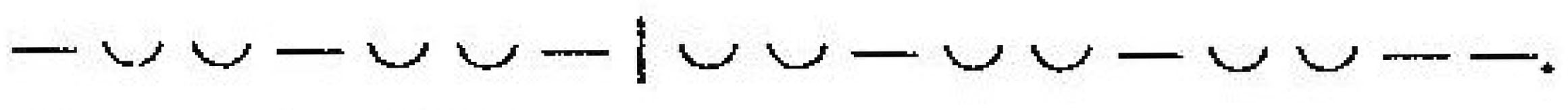

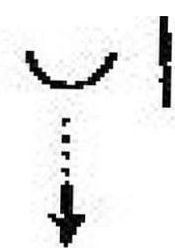

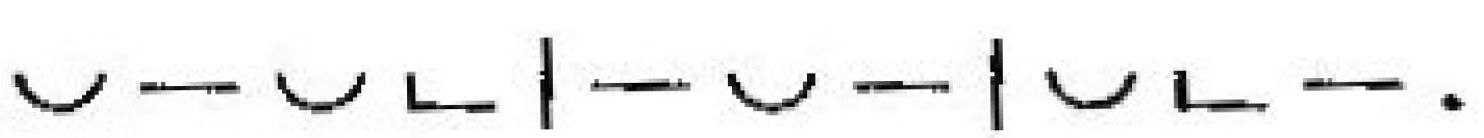

The symbol  marks where the sledgehammer did not strike the anvil. The dochmiac produced by a simple working mechanism takes on an ethical and aesthetic value in the tammurinu and in the funeral rite that it accompanies, which is not found in the anvil music. Each time the last rites are carried in a procession to the dying, this sorrowful rhythm resonates in every one of Sicily’s little villages. marks where the sledgehammer did not strike the anvil. The dochmiac produced by a simple working mechanism takes on an ethical and aesthetic value in the tammurinu and in the funeral rite that it accompanies, which is not found in the anvil music. Each time the last rites are carried in a procession to the dying, this sorrowful rhythm resonates in every one of Sicily’s little villages.

In Salemi, the humble processions of shepherds and farmers proceed in faltering steps to this motif:

Here we have the rumble of ensuing death, the decomposition of life and organic eurhythmic movements into nothing. Faced with the dying person, pain suddenly reappears as the fundamental law of this world; the choir’s emotions are so intense that the swaying bodies form an irregular tripody, which is the dochmaic, an oblique dance; the rhythm arises between one tripody and another.

The plasticity of the rhythm is found in its very name: proof is offered by yet another tammurinu beat which accompanies the sciancata [lopsided] mimicry of the mastru di campu [a Carnival mask] in Palermo’s traditional masquerade:

The motif that accompanies Salemi’s last rites is a thetic form of dochmaic, which is rather more pessimistic and sorrowful than the anacrusic form, typical of the Greeks. The thetic form is found every now and then in tragedies, mixed with the other forms (Euripides, Orestes, I):

Another common feature in the dochmiacs of Greek tragedy is the irrational breve after the syncope and the tribacchus at the end of the tripody (Euripides):

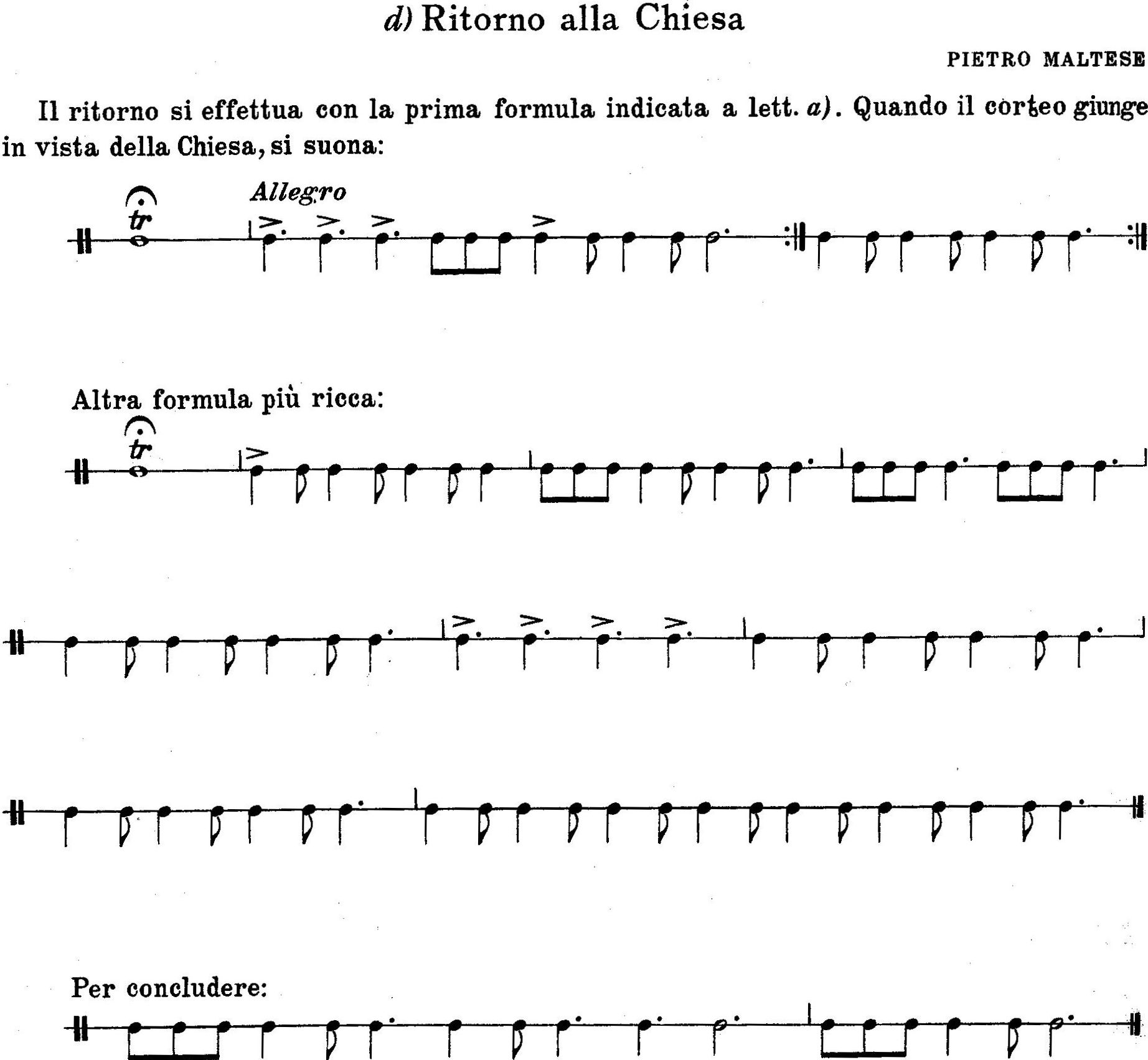

Once the sad rite has been accomplished, the cortege makes its way back to the village. As soon as the church comes into view, the funeral dochmaic is replaced by a festive march, “because seeing the house of God metti alligria” [brings joy to your heart]: only in God do we find joy and happiness:

In Aeschylus’ tragedies, the dochmaic is the only rhythm used in every situation where death and destruction appear to be the only possible and fatal solution of some kind of conflict. The choir of Theban maidens sing in dochmiacs in Aeschylus’ Seven, when from the tower on high they catch sight of the innumerable army that floods the plain in clouds of dust, and the galloping horses who rush forward like a flowing stream, and the charioteers who circle the walls, yelling and shouting while the seven dukes march haughtily on the seven gates. The terrified choir of virgins, beside themselves with fear, beg and scream and plead with the gods of the city to save them from the horrors of war, in a magnificent dochmaic maiden’s song, which could also be said to represent the death song of the glorious city of Cadmus:

Still reeling from their horrible flight from marriage and choosing death over dishonor, the daughters of Danaus sing in dochmiacs as they wander around the rocky shores of Argos and beg protection from the king of the Pelasgians:

A dochmiac example in Sophocles is the Kommos in Antigone (VIII, 1261–1347). However, the pattern of the old dochmaic dithyrambic style is found in Euripides’ Bacchantes, when the chorus of Maenads celebrate the death of Pentheus:

The tragedy takes its double genre rhythms from the primitive dithyramb: other rhythmic forms are the syncopated form of the bacchiac dipody which I found in a tammurinu motif in Naso (Messina):

This is the thetic form of the bacchiac tetrameter found in Greek tragedy:

I have also found the bacchius in dances from Partanna (Trapani); it is a type of bacchanal dance, whose essential feature is the syncope, like a heavy fall to the ground out of time.

These strange elements still persist in Partanna and their nature becomes all too clear if we compare them with Marsala’s light stepping circle dance, which is all choreuses and tribacchuses.

From the dithyramb, we finally arrive at the myth where the origins of rhythm are to be found. When Dionysus-Zagreus was torn to shreds by the Titans, the primordial unity of mankind was destroyed, and humankind was created from the death throes of the God. The ancients replaced a phenomenon with a god, and the cult of this god was the representation of the phenomenon itself, whose motifs were reflected therein. Thus, in the cult of the god Dionysus, double genre rhythms were a direct representation of telluric phenomena and linked to the formation and catastrophic destruction of worlds. Aeschylus says this in a passage on the primitive dithyramb: “The drum rolls, like thunder rumbling underground, spreading great terror”. Telluric events periodically reoccur on this earth of ours as the centuries go by, and this renews the dochmaic sense of life in every one of us. The dithyramb is still alive and kicking and, together with its rhythms, has emerged from the very bowels of the earth that was shaken and overwhelmed. Therefore, nothing has changed. From underground, the Eumenides cursed the Gods of Olympus in dochmiacs. And even today, we shed heartfelt tears and continue to curse the ironic fate of this land, where beautiful things are created and destroyed at the whim of some God or other!

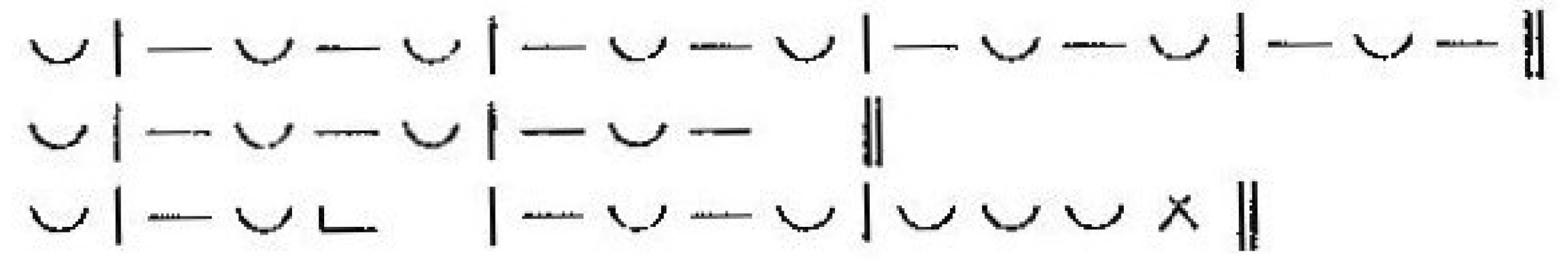

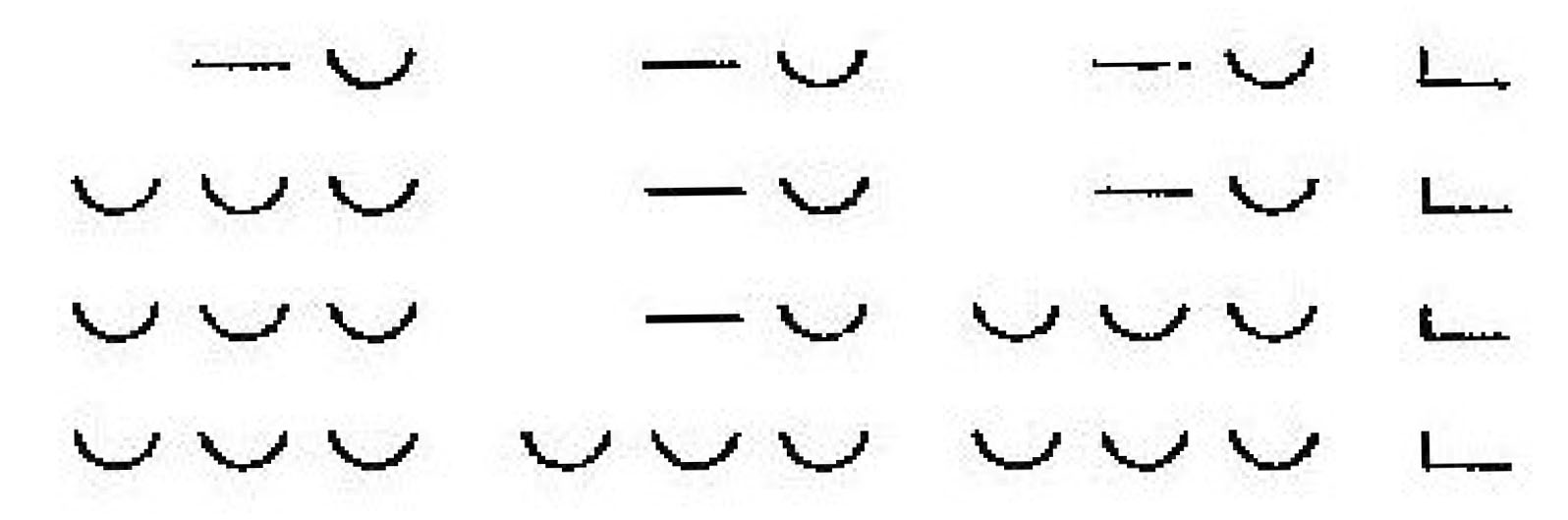

Therefore, the opposition between equal and double-genre rhythm is not merely a question of metrics, but it exists in life itself, in the dynamics of things; it is the opposition between the spiritual and material world, between heaven and earth, between Apollo and Dionysus. Dactyls have an innate tendency to be symmetric, because this is how one limits the effort involved in achieving one’s aim as quickly as possible; this symmetry is sought after and obtained right from the basic unit of measure: the foot. On the contrary, in double-genre feet, there is no equivalence between successive movements, and symmetry is only achieved between groups of two or more basic units. The iambs and trochees are grouped in dipodies with stress on the first or second foot:

The metricists’ interpretation corresponds to the plastic, spontaneous, and unconscious nature of the cyclical form. Anna jumps in a cyclical rhythm, hopping on her left foot during the thesis and landing on her right during the arsis.

In the trochee, the arsis is the upward movement, while in the cyclical form, it is the fall and has a secondary stress.

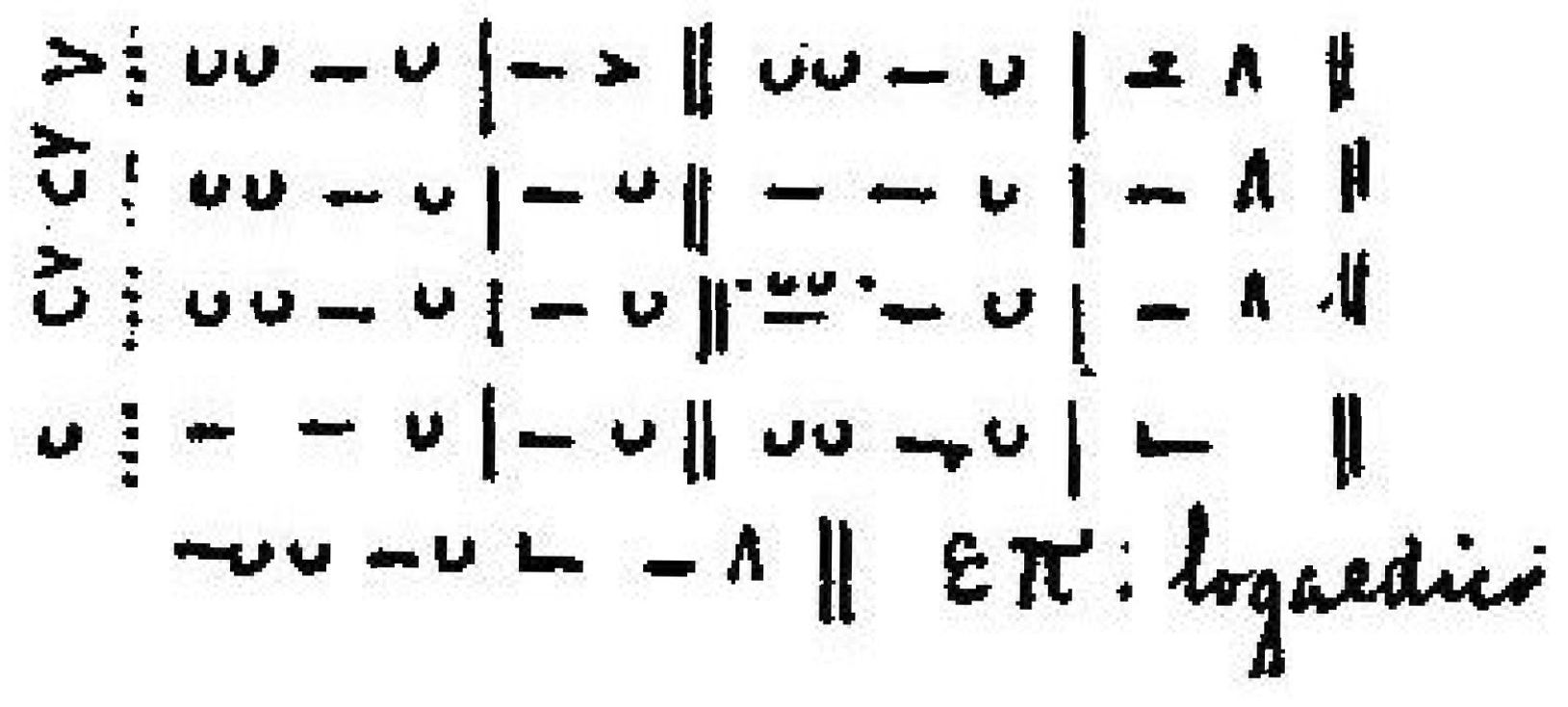

In Sicily, all the logaoedic forms are found in the tammurini, the tammureddi (tambourines), the friscaletti (beaked flutes) and the ciaramedde (bagpipes). The following Jolla from Salemi is played on a three-hole pipe:

But Aristophanes is the poet who preserved the archaic Greek logaoedic form, “the aria from the ancient golden age, to be performed in a rustic manner”. (Thes.) He mainly uses the squared glyconic quatrain, which is so easy and full of momentum, with the typical Greek brachi-catalectic:

Another meter of this kind of lighthearted song is the first pherecratic with anacruses, which is as lively as the ancient village sikinnis [satirical dance]:

* * * Although this essay has served my intended purpose of providing information about the topic, it has merely scratched the surface. Of course, we have an extremely limited knowledge of this primordial musical world. In the best of cases, Italian culture has looked no further back than our Renaissance classics, whenever it has actually stopped its wild-goose chase through the music of every country. Our culture has overlooked what is most vital and essential in all of us and has ended up as sterile rhetoric. However, if we leave aside all these kinds of developed music and put our ear to the ground, then we will be able to hear the perennial sources of Italian melody, the immortal song of our land, which has long been waiting to make its entrance into art and to enrich it. The simple feeling of something that is new and refreshing is exactly where the nobleness of our work lies: the gathering and bringing this material to light with the supreme goal of creating our national art, and of thereby providing a harmonious and glorious image of our way of life. The creation of this direct relationship between culture and popular life is a decisive step towards solving our artistic problems. However, it cannot be limited to providing superficial notions of an isolated fact or offering mere historical notions of this and that. It has to go above and beyond history, looking deeper into the distant past and far-off future of the full and integrated life of the Italic peoples that emerges from the dark ages and from folklore.

From such a distant perspective, many things that are given far too much importance today will remain obscure, while simple and essential truths will be brought into the open. All of a sudden, we can rid ourselves of the prejudices of the mannerism that we have been used to seeing as the final form of music; any developments in our art are no longer seen as essential, but are instead a way of being and a style that can also change. And it is this sense of life, beyond the fortuity of a determined time that contains the energy that springs forth from the depths of our soul and drives us onwards in the infinite spiral of our development. This is the world of instincts, the world of positive forces that go to create a nation, and it is the only place where art and our lives can find the bases and the core-matter of a true culture.

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

etc.

etc.

etc.

etc. etc.

etc.

) and the choreus to the cretic.

) and the choreus to the cretic.