|

Maloya Music as World Cultural Heritage: The Cultural, Political, and Ethical Fallout of Labeling Guillaume Samson Originally published as “Le maloya au patrimoine mondial de l’humanité. Enjeux culturels, politiques et éthiques d’une labellisation.” Cahiers d’ethnomusicologie 24, 2011, 157–171. Draft translation: John Angell, copy-editing: Kristen Wolf. Preface by the author (June 2015) I wrote this article three years after the inscription of maloya on the representative list of the UNESCO's Intangible Cultural Heritage (ICH). Since the original publication of the article, the relevance of this inscription has continued to be discussed in the Réunion cultural world by mobilizing the kind of arguments that I present in this paper. The debate was recently extended to the Indian Ocean with the inscription of the Mauritian séga tipik on ICH and the Seychelles’ steps to make the moutya a candidate. These inscriptions demonstrate a logic of cultural competition that takes place between territories around ICH. Following this logic, the inscription tends to hide regional musical diversity (comprised of historical affinities and contemporary circulations) in favor of a monolithic approach of stereotyped musical identities. In this new context, the cultural competition that I observed on Réunion Island in the aftermath of the registration of maloya has been recently revived on an international scale. Abstract In October 2009, the maloya musical style of Réunion Island was enshrined as part of the UNESCO Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity (ICH). Locally, this labeling is now part of an ongoing cultural and political struggle that has characterized the island’s music scene for forty years. Participating in its change of status and thus participating in its “emblemisation” the enhancement of maloya by UNESCO has unleashed an occasionally brutal debate about the collective identity of Réunion Island. The debate challenges the conceptual framework and ethical principles of the UNESCO Convention for the Safeguarding of the ICH. After describing the various dimensions of the problem and the shifts in the island’s cultural balance of power that followed maloya’s ICH designation, this essay offers a critical analysis of the scientific and institutional positions underlying the processes involved in the application of such labels. Questioning the “integrity of traditional cultures” (Abelès in Appaduraï 2005) is a direct consequence of globalization[1] and one of the most important factors driving contemporary efforts to preserve the world’s diverse cultural practices. This mission to preserve or safeguard informs the current policies behind the UNESCO ICH program. In response to the imperative to “maintain cultural diversity” and foster “inter-cultural dialogue,” safeguarding “inherited traditions and living expression” is intended as a means of resisting newer forms of cultural domination and alienation. It is ultimately seen as a means of encouraging peace and “social cohesion.”[2] The goal is to enable the survival of the oldest and most local cultural heritages in the midst of the new global culture. This is in turn grounded in the assumption that the “groups” through which these cultures and practices exist consider their heritage to be a key aspect of their identity. The 2003 Convention for the Safeguard of the Intangible Cultural Heritage[3] and the various public pedagogical documents concerning the ICH and its application specifically emphasize the pivotal role of “communities,” which must participate in promotional events as stakeholders: “The Convention focuses on living expressions of the intangible cultural heritage seen as significant by the communities. These expressions produce a sense of identity and continuity.”[4] “Communities” are considered to play a central role in guaranteeing the relevance, effectiveness and morality of activities surrounding the ICH, based on the assumption that the groups that transmit cultures become the actual instigators and key actors in the preservation process. On paper, this guiding principle appears unassailable. It stands as a bulwark against cultural misunderstandings and the risks of misappropriation, at the threat of reducing the bearers of the culture to becoming neglected instruments (Aubert 2010). If the “community” and “group” are considered the primary, if not the only, frame of reference for identifying and promoting heritage cultural practices, the question is whether the convention commits a mistake by unilaterally siding with culturalism? The idea that there is a correspondence between a particular form of cultural expression and the community or group that sustains it – and whose aspirations, linked to identity, are limited to culture – is the principle underlying the ICH. This position has the potential to yield an impoverished vision of the political, cultural, social, or economic stakes that are inherent in the construction and negotiation of group identities in the contemporary world. The tenets of the ICH offer an idealized image of a harmonious cluster of relatively homogeneous communities working together to preserve a shared ancestral culture. Applying this set of beliefs to the Réunion context raises the question of whether it should be applied to “works of the imagination” (Appaduraï 2005, 32–42) or to the questions of identity that are associated with them.

The questions that I have raised here regarding the elevation of maloya as part of the ICH, center on two key concepts that the labeling process adversely affected intercultural dialogue and social cohesion. My intention is ultimately to interrogate my own role in the labeling process in order to argue that the entire role of scientific research in promoting cultural heritages needs to be re-examined.

A year later, when I heard that maloya had been selected for recognition by UNESCO, I felt a certain sense of satisfaction that I had contributed, however modestly, to the successful application and the recognition of this important element of the musical heritage of Réunion Island. In the light of the fallout of this recognition on the island, however, and the virulent debates that have surrounded it, I began to question myself about the potential impact of such high profile labels on the musical diversity and cultural life of the island. These questions understandably dampened my initial enthusiasm.

In re-considering some of the cultural, political, and ethical aspects of maloya’s newfound status as part of the world’s cultural heritage, I am not in any way attempting to distance myself from a process in which I was involved or to condemn after the fact a form of cultural recognition that seems entirely legitimate. My purpose is instead to call attention to certain problematic aspects of musical labeling, while also re-considering the role of research organizations in this kind of “study.”

The right-wing party in power supported the idea of Réunion Island as a French department. They were opposed by a cluster of pro-autonomy, far-left, and pro-independence groups that included the Parti Communiste Réunionnais (Réunion Communist Party – RCP), as well as a number of other organizations (including the Front de la Jeunesse Autonomiste de La Réunion (Réunion Island Youth Autonomist Front – FJAR) and also the Organisation Communiste Marxiste-Léniniste de la Réunion (The Réunion Island Marxist-Leninist Communist Organization – OCMLR). This opposition between right and left masked deeper disagreements about how the island should be governed; discord that in turn revolved around a range of cultural attitudes (Samson 2006). Along with the Creole language, music was one of the components of this political polarization. Until the 1960s, Réunion music had essentially been represented in the media and official discourse by séga (Creole songs played on modern instruments) and by a folk dance repertoire. The more significant media profile of séga continues to this day. As séga lacks any true ethnic or community associations, it was perceived as consistent with a series of practices, particularly balls and talent shows, which were able to reach every segment of the island’s population. Maloya, on the other hand, was more openly linked to sugar plantation workers who were descendants of slaves and other laborers of African or Malagasy origin and to a lesser extent, from India. Maloya was not particularly prominent in the media, occupying only a very indirect and anecdotal public profile. At the time, maloya essentially existed within communities and families, and through the diverse practices that it was known for, including maloya balls, ancestor worship, and moringue, held only a minor position in the island’s overall cultural hierarchy. In its most “archetypical” musical form – vocals alternating with soloists and choral groups, drums, improvised rattles, and idiophones –, maloya differed considerably from séga, although both forms share significant rhythmic and melodic similarities.

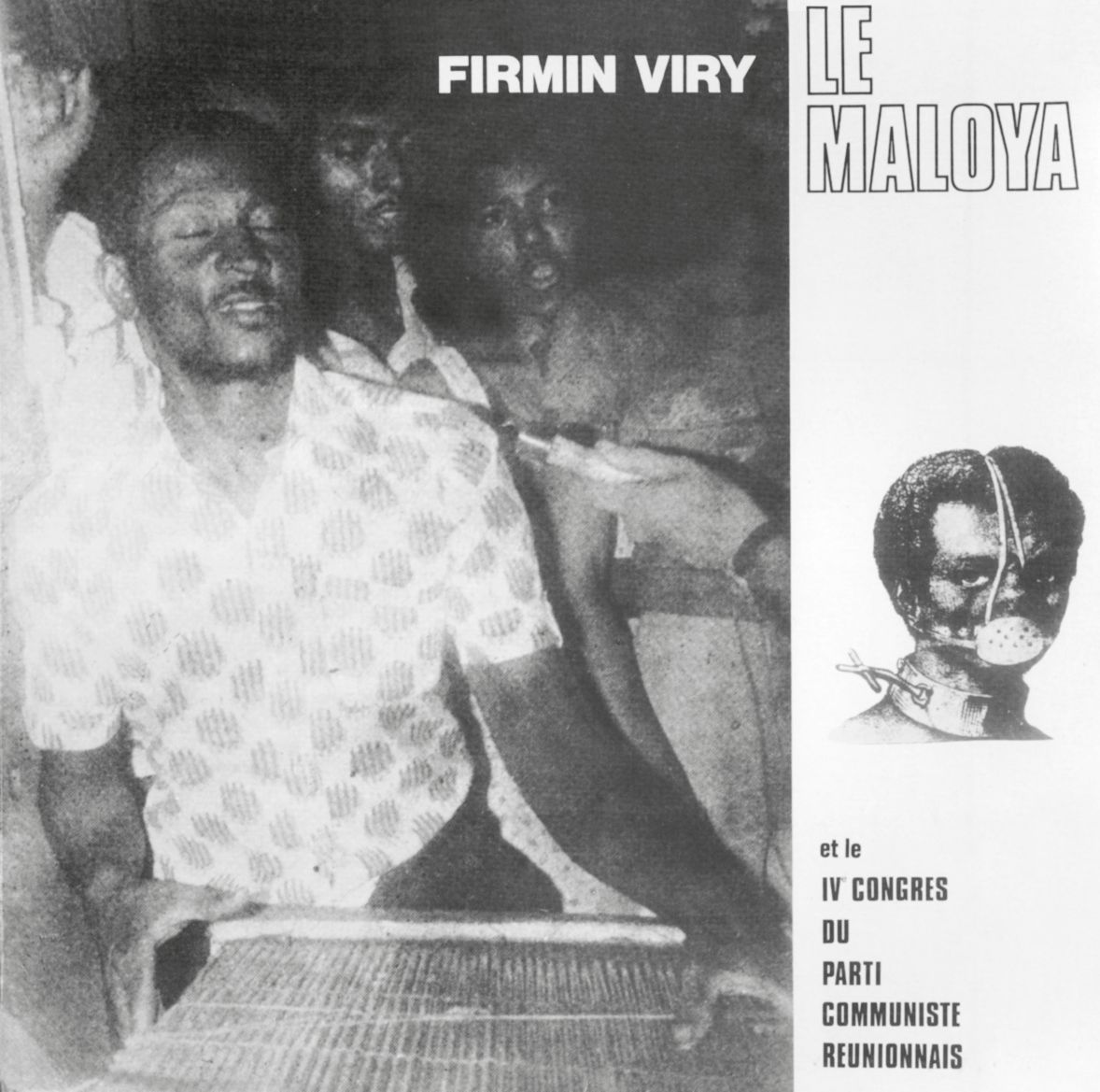

In the 1970s, the RCP designated maloya as its official music, recording two maloya albums during the Party Congress in 1976. This moment marks when the competition for representation between séga and maloya became more and more intense, as the political influence of the RCP increased and maloya garnered a correspondingly wider public. In speeches by leftist activists, séga became the symbol of cultural assimilation, urbanity, and even collusion with “departmentalist” power (as well as the neo-colonial ideology associated with it), while maloya symbolized cultural resistance, a rural lifestyle, the voice of the poor and the rebirth of the “Réunion Island people.” Although this binary opposition was somewhat rooted in reality, it was primarily tied to activist and cultural discourses that promoted an exclusivist view of musical representation. The strident political struggles made it impossible to imagine cohabitation between séga and maloya (although this was true of the island’s entire music scene). To a certain extent, maloya was seeking to supplant séga as the “national” music. Despite the adoption of maloya by folk groups closer to the right wing in the late 1970s, the polarization of the two forms deeply influenced the Réunion music scene in the ensuing decades (Desrosiers 1996). Today, both forms are part of an alternative form of culture and identity which were revived when maloya was listed as part of the ICH.

Despite generations of institutional change and increasing openness, maloya continues to occupy an ambiguous position. In addition to being promoted in terms of cultural identity by island institutions, it also plays a prominent role in the musical export policies related to Réunion Island. Since the early 1980s, maloya has also deeply influenced other new musical styles that involve different forms of fusion, which include malogué (maloya-reggae), electric maloya, raggaloya (ragga-maloya), jazzoya (jazz-maloya), and maloya raï. A few neo-traditional maloya bands currently also enjoy considerable success on the island. Nevertheless, as is revealed by sales of the island’s recording industry, the most popular local musical genre continues to be séga and, to a lesser extent, Réunion ragga dance hall. These genres dominate record sales as well as radio and television music channels. As I have argued elsewhere (Desroches and Samson 2008), maloya is a musical style that bears meanings related to identity and memory, while it continues to occupy a marginal position in the island’s music industry. This marginality can partly explain its institutionalization and the fact that, despite local and international visibility, maloya continues to carry a message of resistance.

Despite the fact that the program claimed that it would include every component of the island’s cultural history, the priority, again according to Paul Vergès, was to pay tribute to “more than a century of generations of slaves”. The building was intended as a place to house a museum that would serve as “a mausoleum for these martyrs” and as “the first great homage to those who were offended, humiliated for centuries”. For Vergès, this was consistent with a historical duty to remember, which would help compensate for the historical injustices suffered by the majority of the people of Réunion Island. These arguments underpinned the MCUR’s commemorative policy, which embraced the view that unity was impossible without recognition of the traumas suffered by the majority of its ancestors. Unity also depended on the promotion of cultural production, most of which was intangible and was created by the oppressed majority. As a way to crown these efforts, in 2004 the Region and the MCUR created an honorific title that would acknowledge the “contribution of a man or woman from Réunion to the preservation, promotion, creation, or transmission of Réunion’s intangible cultural heritage” (MCUR 2009). The title, which in Creole translates as Zarboutan nout kiltir (ZNK), is best expressed in English by the expression “Pillars of our culture.” Between 2004 and 2005, five maloya musicians received the ZNK title, followed in 2009 by Tamil ball[7] singers and moringue[8] dancers. The purpose of the commemoration was to highlight oral traditions and intangible heritage, which had not been officially recognized by state, regional, or departmental cultural institutions. As a consequence of this perspective, no séga musician received the ZNK title during the MCUR commemorative program.

However, over a period of approximately two decades a number of séga musicians were appointed as “Chevalier dans l’ordre des Arts et des Lettres” (Knight of the Order of Arts and Letters) or “Ordre national du mérite” (National Order of Merit). Some also were awarded SACEM medals, and recordings that they had made between the 1950s and the 1970s have been re-recorded and published under the Takamba label, under the sponsorship of the Regional Pole of Contemporary Musics (PRMA). Due to their well-established reputation, séga musicians were excluded from the MCUR’s cultural rebalancing efforts. Although not currently as strident as it was in the past, the competition between séga and maloya was implicitly visible in the Regional Council project, which, despite its claims to embrace “ecumenical” cultural objectives continued to uphold communist cultural-activist positions dating from the 1970s.

Echoing this title, an article on the Regional Council’s website announced the nomination of maloya by asserting, “Maloya becomes part of the UNESCO world heritage. An acknowledgement of Réunion Island culture.”[10] This title suggests that when maloya became part of the UNESCO world heritage, the distinction represented an acknowledgement not merely of the music but of Réunion Island culture as a whole maloya. As in the title of the RCP album, a synecdoche was transforming maloya into the musical symbol of Réunion Island. The headlines of Témoignages (a newspaper close to the RCP) similarly crowed “33 years after ‘Peuple de la Réunion, people du Maloya.’ A new victory in Réunion Island struggle: Réunion Island maloya as part of the world heritage.”[11]

One intrinsic element of political action, voluntarism, quickly became a target for opponents of the cultural and remembrance positioning of the region and of the MCUR.[13] The first argument for opposing the designation of maloya as ICH was specifically related to the prominence ensured by the ICH label in comparison to the many other musical forms present on the island. Indeed, a number of opponents wondered why among all the local musical styles present on the island, maloya, should be singled out for such a distinction. I attended a Tamil ball in October 2009 in a Hindu temple on the western part of the island. The priest who was in charge of the temple and known for his cultural activism in favor of recognition of popular Hinduism on Réunion Island in the 1970s, lamented the fact that the audience that attended the performance was not larger. In his speech, he unhesitatingly broached the question of maloya, calling out to Danyèl Waro, a famous maloya musician in the crowd that evening: I want to say something. You have heard that, in the media, they have announced that maloya is the Réunion Island culture, the whole of the Réunion Island culture. We cannot blame those who do maloya. Look at Danyèl Waro who is with us this evening, he is the king of maloya in the Réunion Island and he is with us to bring this Tamil Ball to life. If the State does not recognize the Tamil Ball today, it is because of us, the people of Indian descent, who reject our own culture. We are lazy, we sent out two thousand invitations for this ball and almost nobody has come. Whereas when the maloya people hold their parties, people go and listen. We, the Malabar people, wait passively for the State to recognize us. But we do not realize that when the State recognizes only maloya as Réunion Island culture, tomorrow, and whatever the political power at the head of the country, the Malabar will be treated like nobodies. Whereas if the Malabar were brave and came to listen to the Tamil balls, the politicians in power would have recognized us, just as they recognized maloya.[14] The priest’s views reveal the way in which the labeling of maloya has taken on unintended local implications. Two important points are made in this speech that reveal a process of reinterpretation whose effects appear to contradict the stated objectives of the ICH, including intercultural dialogue and social cohesion. The first issue concerns the priest’s statement that recognition by national and international organizations has lent a form of cultural exclusivity to maloya, despite the fact that other musical heritages also deserve to be promoted. The second issue is a direct consequence of the first and involves the connection between music and collective cultural representation. From the priest’s perspective, maloya’s recognition by UNESCO made it into the symbol of “the entire Réunion Island culture,” in turn endangering the cultural heritage of his own community (the descendants of Indians) unless the community promotes itself more successfully. maloya’s coronation makes it appear to have been formally recognized by the entire island’s musical culture. It is noteworthy that this same priest was awarded the ZNK title by the MCUR in 2008 and that it was also awarded to Tamil ball musicians in 2009. But the UNESCO label, which the priest considered analagous to the government in his speech, is clearly more symbolically powerful than local or regional honorary titles from the MCUR or the Regional Council. For this reason, the ICH label is seen by the priest as part of a cultural and sectarian competition in which he is a participant because of his role in seeking to the Malabar community’s attitude towards their own heritage.On a more controversial level, Ladauge, a historical member of the Réunion folklore movement, publicly complained about maloya’s newfound status which had been exploited ideologically through the use of arguments surrounding its “emblematic” role and its ICH designation: What always surprises me is seeing only maloya and not séga in the UNESCO heritage. Maloya, historically, is a form of séga […]. That is the name we gave to slave dances. It was a shout of support for all the people of Africa […]. It was the basic rhythm of our different styles of music and the only difference between them is the tempo. It is a shame that for political reasons maloya was made into an instrument of hate, violence and racism that continues to lay waste to Creole culture.[15] This speech is further evidence of how the labeling of maloya is interpreted inside the framework of musical representativeness and the cohabitation of the island’s musical cultures. By gaining international recognition, maloya automatically became a symbol of the entire community at the explicit expense of séga. Like the priest’s perspective, the problem that Ladauge sees with this interpretive frame is the exclusivity that it attributes to maloya. According to what criteria should one form – maloya – be specifically valued against another – séga? The person who expressed these views was revisiting one of the sensitive points in the conflict between séga and maloya. She believes that maloya and séga belong to the same musical culture, and further, that maloya represents to some extent an outgrowth of séga. In fact, until the early twentieth century, the word séga was used to describe both the music of the descendants of African and Malagasy laborers, currently called maloya and Creole songs, which today are known as séga. Only in the twentieth century, beginning in the 1930s, did the terms begin to be applied as they are today.[16] Ladauge is thus using the history of these categories and the rhythmic similarities between maloya and séga as a means of questioning the distinction between the two genres. By reasserting the historical primacy of séga (of which maloya is a variation in her view), she is implying that séga has a more legitimate claim to a more elevate status. Despite its partisan character – Ladauge is a fierce opponent of the RCP – this position helps reveal the problems associated with the high-profile labeling of cultural objects. Her perspective is particularly helpful in signaling the fact that it is not always clear how the actual “communities” themselves view and define their own “musical cultures”.

One final strand of negative reactions to the ascension of maloya to ICH status deserves mention. I had the opportunity to engage in a conversation with a locally famous séga composer and musician who performed at balls and recorded in studios in the 1960s and 1970s. He was named a Chevalier des Arts et des Lettres in 2007 and was an important member of the SACEM in the Réunion Island. For this reason, he was in attendance at the ZNK awards ceremony in October 2009, which was held at the Saint Benoît Music Conservatory and organized by the Regional Council of the island and the MCUR. Maloya (which had just been awarded the ICH label) was obviously in the spotlight during the ceremony, but Tamil balls and meringue were also featured. The awards ceremony featured speeches by Paul Vergès and Françoise Vergès, who focused on the philosophical underpinnings of the MCUR project using words like “reparation,” “decolonizing consciousness,” and “acknowledging the remembrance of slavery”. There were also musical and choreographic performances maloya, Tamil ball, and moringue) during the event. After the ceremony, our conversation became more solemn, and the ségatier[17] expressed his personal opinions and, after some hesitation, said: “All of this is fine… but why always dwell on these stories of slavery and suffering?” By revealing his discomfort over constant references to slavery and reparations, my interlocutor was also sharing his reluctance to constantly answer the call to honor the “duty of remembrance.” His views are common on Réunion Island and are often referred to as a way of distancing oneself from certain kinds of cultural activism that are seen as focused exclusively on the past or tied to particular political ideologies.

The labeling of maloya revealed a number of problems inherent in the conceptual and ethical frameworks of the 2003 Convention for the Safeguard of the Intangible Cultural Heritage that created the ICH, particularly with respect to the post-colonial and multicultural context of Réunion Island. First, it seems obvious that promoting a specific, long-under-appreciated facet of a cultural and musical whole at a particular moment risked being perceived as negating the importance of other components of regional culture. As a consequence, the sectarian reactions on the part of other cultural groups and forms of expression that were triggered by the ICH label are completely understandable. The impression that they had been left out of the process led every community to proclaim its own cultural supremacy. The obvious danger in such a case is that instead of helping to ease cultural tensions, the labeling process can potentially heighten partisan resentments that, in specific contradiction of its intended purpose, foment rivalries instead of promoting dialogue. The designation of a single style of music as the musical culture runs the risk of impoverishing the entire cultural spectrum; it is just one among many possible access points to this multivariate culture. Another obvious risk in the case of maloya relates to the relationship between remembrance and community-specific values. With maloya, it seems legitimate to ask the community that represents it and proclaims its importance whether it is representative of all of the inhabitants and groups of the Réunion Island, including those who identify themselves as descendants of slaves and activists. In other words, is a clearly identifiable group associated with maloya? If so, what are its boundaries and distinctive traits – Color? Social status? Cultural practices? Political affiliation? A shared sense of territorial belonging? In light of the uncertain position of maloya in the island’s cultural field and the complex and even violent debates surrounding its position, a categorical but judicious answer to these questions is very unlikely. Whether in speeches tinged by negationisms or amnesia, or by historical revenge, the mobilization – for sectarian or political purposes – of group- and community-based identities opens the way to possible abuse of remembrance (Todorov 2004). In a similar way, the objectification and exploitation of memory mirrors the positions of persecutors and victims in colonial times, positions that are readily apparent in these cultural conflicts on Réunion Island. Objectification provides fertile ground for essentialist positions and discourses, which in turn gravely endanger cultural dialogue. Although the reflections contained in this essay should prompt the various actors to reconsider their positions, my perspectives are absolutely not intended to cast doubt on the rank of maloya as part of the ICH or, more generally, on the promotion of the island’s musical heritage. My remarks are instead directed towards the contexts and the conditions under which labels such as the ICH are decided and the potential – and often unpredictable or undesired – consequences of such designations. Efforts to restore cultural balance, which were and remain entirely legitimate in the context of Réunion Island, inevitably engender conflicts and confrontations. It is quite possible that critical re-assessments such as the present essay are a secondary benefit of efforts to establish a cultural balance, promote cultural remembrance, and revitalize heritages. If, rather than being denied or exploited, the energies generated by critical reflection could be turned to constructively uses, the negative cultural backlash of labeling might eventually have more positive outcomes than if they merely fuel partisan speeches and commemorations, as is currently the case on Réunion Island. The researchers, collectors, and bureaucrats who participate in efforts to restore cultural balance could play a positive role in the labeling process. Their perspectives on the contemporary cultural, political, and sociological dimensions of a music scene could better inform selection processes such as the ICH. A more inclusive selection process might also anticipate the unintended “drift,” exploitation and layered misinterpretations such as those that were triggered by UNESCO’s labeling of maloya. Local research programs can provide a kind of “sociological monitoring” and provide grounded observations about the impact of labels on specific cultural domains. Helping them to anticipate and understand these secondary consequences of labeling would enable cultural institutions to more effectively manage the aftermath and direct their energies in constructive ways.

It seems both appropriate and important for science – particularly ethnomusicology – to contribute to commemoration processes as well as to the struggle against cultural and social inequalities. The involvement of science in the quest for improved knowledge and greater recognition of the diversity of humanity’s musical culture is indeed an exceptionally high calling. It also makes sense for science to support and inform UNESCO’s general orientations regarding diversity and cultural dialogue. As this critical review of the fallout of maloya’s ICH designation has shown, however, social scientists should be highly vigilant about our own roles in these processes and about the ways in which the knowledge that we create is used. It is also clear that we must remain attentive to the institutional and political environments in which we conduct our research.

|